It’s about nine thousand miles from Maryland to Myanmar, and it’s a route Tatiana Loboda knows well. She’s part of a team developing the Myanmar Malaria Early Warning System (MMEWS), which forecasts malaria hotspots in an effort to guide malaria treatment and elimination activities.

Loboda’s team collaborates with the Duke Global Health Institute, and the work is supported by the Applied Sciences’ Health and Air Quality program area, the National Institutes of Health and the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. One goal of MMEWS is to expand the satellite-based malaria forecasting to include human population data — like density and socio-economic status. To get the full picture, Loboda and her team spend a lot of time on the ground gathering information about the Myanmar people to inform their work.

“Before I can build a broader theory of occupational exposure, I desperately need to collect as many ‘case studies’ as I can,” said Loboda, who works in the Department of Geographical Sciences at University of Maryland, College Park, Maryland. “That’s essentially what I’m doing when I travel. I learn what people do, how they move across the landscape, how they think they get exposed to malaria and when, and most importantly, with each trip I develop a better understanding of what questions I need to ask next.”

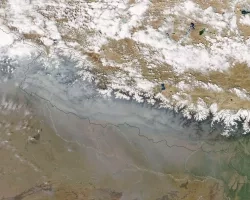

To create a map of land cover and land use relevant to malaria, the MMEWS team uses data from the Landsat and Sentinel-2 satellites. These data help them understand where people are, what they’re doing there and any changes to vegetation throughout the year. Loboda’s team uses this information to estimate how many and what kind of mosquitos are present in certain areas, how and when people come into contact with them and if communities are at risk.

In addition to satellite data, Loboda also uses her five senses to gather important data as she travels around Myanmar, building a database of knowledge to use for the malaria forecasting application. Here's her experiences in Myanmar in her own words.

Sense #1: Touch

"I don’t generally get to touch elephants in Maryland. Elephants are so gentle, and it’s tremendous to feel their trunk. [When they touch you], their touch is very gentle. It’s like a child’s touch."

Sense #2: Taste

"One of my favorite things to eat when I’m in Myanmar is whole steamed fish in lemon sauce. It’s so good! I also enjoy fish crackers and prawns during my travels there. The primary eating implement is a spoon. You have a fork and a spoon as your cutlery for any meal, and you actually use the fork to put food on your spoon. There’s no knife so you have to tear up pieces of meat with your fork and spoon."

"Myanmar food is extremely spicy — even foods they say aren’t spicy are hot. I like spicy food so I can appreciate it but if you don’t like spicy foods, there are very few things you’ll enjoy eating in Myanmar."

Sense #3: See

"I love seeing the pagodas. They’re absolutely incredible. They’re so beautiful and they mean so much to the Myanmar people. There are thousands and thousands of them, all different shapes and sizes. The pagodas are all about faith, and about people’s connection to their heritage and ancestors. During the dry season, the sky is so blue. It’s very, very bright there during Myanmar’s dry season. I was in Myanmar for five weeks during monsoon season, and I saw an hour and a half of sunshine that whole trip. The rest of the time it was just continuous rain that varied from a drizzle to a downpour."

Sense #4: Hear

"You’re constantly hearing the preaching monks in Yangon. They have loud speakers in their trucks, and you can hear them from miles away. People in Myanmar use their car horns liberally. It’s almost like a language in itself. It's constant, nonstop honking but the honks mean different things and you learn to differentiate them. The cars move there like a school of fish. The painted lanes are only suggestions, they just maneuver so fluidly around each other and they’re constantly communicating where they are and what they’re intending to do by honking."

Sense #5: Smell

"My favorite smell happens the moment I land and I’m walking through the airport. I don’t know what the smell is, whether it’s a special cleaning agent used in Myanmar, but the moment I walk through the airport, I know I’m in Myanmar. That smell and the warm, humid air makes me happy. I haven’t encountered it anywhere else. It always makes me smile. And there are only a few things that can make you smile after traveling over 19 hours straight."

"Duran fruit! Bad doesn’t begin to describe the way it smells, but it’s called the king of fruit and is considered the top of the line most wonderful thing. I tried to eat it once at the airport when they were doing little samples. It was covered in white chocolate and I almost gagged on the spot but it’s the highlight of fruit experience, it’s a big part of the culture."