An audio interview with Jason Vargo of the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco.

The smoke from wildfires obeys no boundaries, it crosses state lines and irritates people’s eyes, nose, throat, and lungs. Working at the intersection of climate data and health equity, Jason Vargo, a senior researcher at the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco, uses NASA satellite data to better understand wildfire smoke impacts and build healthier communities.

NASA Applied Sciences’ Marissa Kunerth spoke to him about his work. The transcription below has been edited for readability and clarity.

Jason Vargo: I became much more interested in the sort of bigger populations and how those were exposed to environmental pollution and that's where big data sets and earth monitoring data sets like those that NASA produces became very important to me.

Marissa Kunerth: That's Jason Vargo. He is a senior researcher in Community Development at the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco. Vargo works with two different areas of NASA Applied Sciences – Health and Air Quality and Wildland Fires. Thanks for joining us, Jason!

Jason Vargo: Happy to be here!

I'm here today representing myself so, anything I am talking about today are not necessarily the views of the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco.

Marissa Kunerth: To start, can you tell us about your career path and your role at the Federal Reserve Bank?

Jason Vargo: Sure! Well, I work in community development, so a lot of people don't even really know what that is, but really our mission is to make sure that we are creating an environment that allows everyone to engage in economic opportunities where they live.

A lot of my work has been around places and people and how the places that we live relate to how we live healthy lives and if we can live healthy lives. I started out working in factories and looking at environmental pollution and factories, and that was very interesting. I was looking at sort of where people worked and, and what chemicals might be around them. It was very close – it was like the people were right next to the environmental pollution that they were exposed to. I began to broaden my horizons or broaden my perspective, and I got involved with public health.

And so, I became much more interested in the sort of bigger populations and how those were exposed to environmental pollution and that's where big data sets and Earth monitoring data sets like those that NASA produces became very important to me. So, we could monitor air pollution on the ground on Earth, but we also have satellites thanks to NASA that can monitor these environmental pollutions and air from the sky, from the space and give us a picture of what's going on from above – even in places where we don't necessarily have monitors on the ground on Earth. And those are really what I've been using most recently to sort of think about how wildfire smoke in particular has been impacting communities across the United States.

Marissa Kunerth: So, I know you have two young kids. If you were to ask your kids to describe your work, what would they say?

Jason Vargo: Well, I have a picture actually of what one of them drew. They see my work a lot, they see what I'm working on and now that a lot of people are working from home. But one of them drew this for me, which is their interpretation of a graph that I was working on at the time.

But if you can't read it, it says, “Wow, that's a lot!” And then there are several lines here that represent smoke in California. So, they're learning that I'm working on wildfire smoke, I'm looking at the trend in wildfire smoke over time, and that it seems that in the data that we're looking at in California and the West in particular, it's getting more and more over time – that we're getting more and more wildfire smoke over time. I think that's probably the best encapsulation I think of what they think I'm working on.

Marissa Kunerth: That’s such a great story! Can you take us back a bit? What ignited your passion to pursue a career in climate change and equity, and how did you get to where you are today?

Jason Vargo: Well, I think people who are interested in public health, I think in general, want to help people live healthier lives and that's a motivation for me, for sure.

I've always been interested in climate and the environment and so like I said, a lot of the academic pursuits that I followed focused on this idea about place, where we live, and how that impacts our health. And from climate, you can think about it as the place we live in is Earth and the health of that Earth how does that relate to our own health? But, a lot of my actual research focuses on communities, the community development part of it. So, understanding what are the conditions that people live in, why those conditions exist, is really part of the job and just sort of figuring out how to answer multiple versions of those questions at the same time.

Marissa Kunerth: It’s exciting to hear how passionate you are about your work and helping others!

I’m curious, how do you address the impact of wildfires on climate and air quality through your work with the NASA Health and Air Quality Applied Sciences Team, also known as HAQAST?

Jason Vargo: I was lucky enough to be introduced to HAQAST quite a while ago. Funny story about how I came to know HAQAST was, I was working at the University of Wisconsin-Madison and down the hall from me was an investigator who was heavily involved and really leading a lot of work around HAQAST, named Tracey Holloway. I was like, oh, that's interesting that using satellites and thinking about human health and air pollution, I was like, okay, that's interesting. It wasn't directly related to what I was working on at the time.

I then took a job in California at the California Department of Public Health, where I was working on this again, this intersection between climate change and health equity. When I moved here in 2017, not long after that, there were large fires in the North Bay, and where I live in the East Bay, we were experiencing a lot of air pollution from those fires.

All of a sudden, wildfires were a bigger part of my life than they had ever been before – and a bigger part of a lot of Californian's lives than they had ever been before. So, I became much more familiar with HAQAST and my previous colleagues at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. All it took was just moving across the country and taking a new job, and then all of a sudden, we were working more closely, even though we had been down the hall from each other in the past.

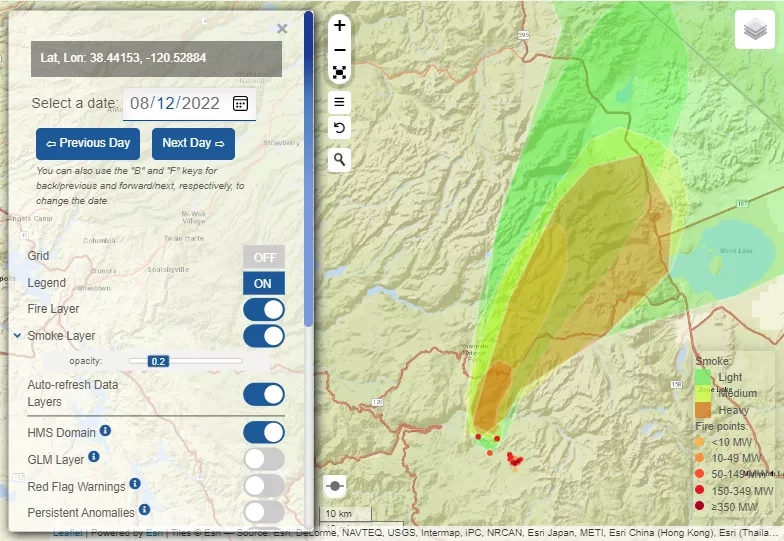

I've been using sort of satellite imagery and products like that, to understand where wildfire smoke is over different parts of the US, different communities in the United States, how long it's been there, how frequently it appears, how dense the smoke is, and then trying to connect that to health outcomes in a lot of cases.

I worked with colleagues at the California Department of Public Health who had been thinking about wildfire smoke for a while. I've used some satellite products that describe wildfire smoke to think about how wildfire smoke has changed over the last 10 to 12 years in the United States. In the time that I've lived here in California, it's a particularly smoky time and the heaviest smoke is appearing more frequently. The smoke is extending farther beyond the fire source and communities are spending much more time under these more dangerous types of wildfire smoke.

With my work at the Federal Reserve, I'm using some of these same products from NASA about wildfire smoke to discuss the impacts on the local economy and really draw attention to the portions of the economy that might be more affected by wildfire smoke. Those are often industries that have a lot of people who work outdoors, and heat is another climate exposure that is very similar in that regard, and these industries have a lot of people working outdoors. If smoke appears or it becomes overly, too hot to work outside, there's a lot of scheduling that may have to change. People may even just cancel projects or lose their jobs. The impact on the economy from these climate risks can be fairly dramatic, and I'm really trying to produce research that helps describe what those impacts might be.

Marissa Kunerth: I bet your career changed drastically when you moved from Wisconsin to California.

Jason Vargo: Definitely, I felt like climate change was much more in my face in California.

Marissa Kunerth: For sure, but every state has its own challenges. In your work, how do you use NASA wildfire smoke data to help protect public health?

Jason Vargo: One way we do that is by demonstrating first with epidemiology studies, studies that look at health outcomes and smoke presence to describe how dangerous it is. So, epidemiologists have recently produced research that looks specifically at air pollution, from wildfire smoke versus air pollution from other smoke to show – or other sources – to show how dangerous wildfire smoke can be for people's health. So those epidemiology studies are really important.

The other way that I use it is to direct or think about where investments might best be placed to help people deal with smoke (Editor’s note: air pollution from smoke). You could think about distributing a bunch of investments or money available for certain projects or retrofits equally across all the population. A lot of my work is to think about, well, would it be better to sort of prioritize the investment of all those resources based on need. Because especially if the goal is to minimize the destabilizing effects of climate on the economy, then we need to understand which parts of the economy, which communities are most likely to be the most destabilized by climate risk and those make more sense for prioritizing those investments.

Marissa Kunerth: Can you provide a specific example from your work where you used NASA’s data and smoke from wildfires?

Jason Vargo: So, wildfires have become a big part of my work and a big part of actually a big part of life for people who live in the West in the last five or six years. I've used some NASA imagery and satellite products to sort of quantify how much wildfire smoke has changed over the last decade. And really, I've been combining again, bringing people into the picture with those environmental data products to try and provide evidence about how many people are being exposed, why it's important to focus on low- and moderate-income communities and communities of color to build resilience and across the economy, focusing on frontline workers who are more likely to be exposed to wildfire smoke in those situations.

So, bringing together data that NASA produces around wildfire smoke and environmental conditions with information that sometimes the Census collects, or local governments may have, or different nonprofits may collect about the actual, the communities and the types of communities that are under smoke more often has been really important for telling that story. And it really helps to center the exposures and the burden of the most disadvantaged communities in our society.

One way that we did that, I mentioned with, in the HAQAST talk I gave a while ago was to think about an intervention that was proposed around improving ventilation in schools, because certainly wildfire smoke events over the last five years in California, Oregon, and Washington, they've been so bad that schools are unable to operate, or people are advised to stay indoors and keep windows closed, etc.

So, improving the ventilation systems in schools was one way of sort of mitigating that impact of wildfire smoke. To do that, I proposed using a record of wildfire smoke over the U.S. that NOAA produces from GOES imagery and satellites that NASA has put up and combine that with information about students and low-income students in particular.

So, we could, we could look at the state of California for example and think about which communities have the most low-income students spending the most time under the most dangerous smoke. Let's prioritize those communities first for interventions like this, that would help keep those schools open.

Marissa Kunerth: That’s a great example of using observation data to improve life here on Earth!

Can you tell us about a time that your work influenced decision makers and policy?

Jason Vargo: Yeah, one way was around fire – not necessarily the smoke part of wildfires, but the burning part of wildfires. At the California Department of Public Health, we had combined information about the likelihood of a place burning in wildfire and the people who lived there. So, we saw the agency, CAL FIRE who's in charge of managing fires and forests in the state, take some of that information and that research, and use it to prioritize which communities they were going to use prescribed burning to help manage fires first.

So that was the case where we definitely saw our research in public health leading to changes in the way that forest management was done in the state.

Marissa Kunerth: Has there been any overlap in your work between environmental health hazards and infectious disease hazards?

Jason Vargo: Yeah, certainly there are. It's been interesting to work on COVID-19 in the last three years, especially during my last year and half at the California Department of Public Health.

The overlap I would say really is around the drivers of disparities that we saw in environmental health and disparities that we saw in COVID. So, the reasons that we saw higher rates of COVID in some communities had to do more with the living situations that people found themselves in, or the opportunities that people had to take time off work, to care for kids, to go get vaccinated, etc., and less about where COVID was spreading the fastest.

We see the same thing with environmental hazard as well, that communities of color, low- and moderate-income communities are more likely to be exposed to air pollution; they're more likely to live in flood plains; they're more likely to be exposed to sources of pollution in their neighborhoods. So, the disparities that we saw in COVID and the disparities that we see in environmental health often share these same drivers that limit the opportunities for living healthy lives.

Marissa Kunerth: How do you think that will change in the next 10 years?

Jason Vargo: Well, I think you're seeing a lot more attention given to those drivers.

There's an old public health parable about people pulling people out of a river and there's an approach we could just keep pulling these people out of the river every time someone shows up and is drowning – like we're going to put all these resources into pulling them out of the river. Or it turns out, if we look a little bit upstream to what the real driver of people ending up in the river is that the bridge is out, we could invest those resources in improving that bridge. So, I think there's a lot more attention being given to these like upstream drivers of where the health disparities are coming from.

You're starting to see that. You saw that a lot during COVID especially assistance in housing, assistance in childcare, those are all important programs that are going to reduce the burden of COVID on the communities that are hardest hit. Even though they're not necessarily like infectious disease specific policies, they really do serve a good, real purpose in reducing the burden of that infectious disease on communities.

Marissa Kunerth: All great points! You’ve had quite the career. If you had to choose, what career accomplishment are you most proud of and why?

Jason Vargo: Well, some of the accomplishments that I think I'm most proud of are the ones that I hear about after I've left them. So, I'm most proud of the things that are sustained once I leave. If I get to be involved at the beginning of something, it feels great, it feels really exciting, but the real rewarding part is to see it sort of live on beyond me and to involve new people, new ideas, and to see them sort of take it and make it their own and do great work with it. Those are the most rewarding examples.

The one I think of often is something I worked on at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, again, where we were partnering the university with communities around the state to work on their problems. So, classwork and professors would devote like a semester of attention to the problems that a city in Wisconsin identified. It was a really great example of how all these ideas and energy at the university could really respond to needs and questions that needed answered across the state. I thought that was a great program, and it's been wonderful to see it sort of live on, and to grow and flourish after I left.

Marissa Kunerth: That sounds like a very rewarding experience! If people listening to this interview only get one thing out of it, what do you hope that is?

Jason Vargo: Some of the most important ideas that I've learned over the last five or six years of working on climate and health in California, and now in community development, like at that same intersection between climate risk and community need at the Federal Reserve – is that it makes a lot of sense to consider people's needs in thinking about how we address the problem.

And to really – again – tell that story about what are the upstream drivers that create need or limit the opportunity for certain communities where we're working.

Marissa Kunerth: Talk about inspiration and impact! Thank you so much for taking the time to talk with us, Jason!

Jason Vargo: Thank you for having me.

Learn more about Jason Vargo’s work at the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco story on the economic impact of disruptions from wildfire smoke or on Vargo’s personal Twitter account named @_vargo.

This interview occurred on 9/23/22.