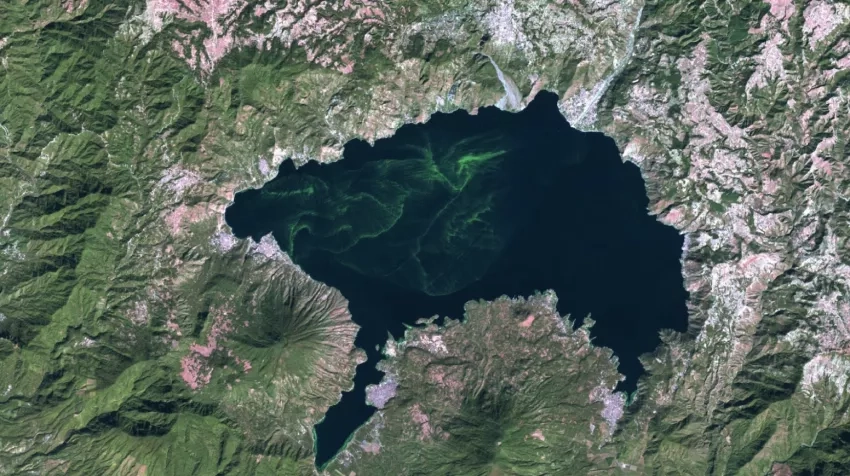

Nestled in between soaring green mountains, Guatemala’s Lake Atitlán is renowned as one of the most beautiful lakes in the world. It is the home of several Mayan communities and is one of Guatemala’s most important tourist destinations. It has also been under threat by massive blooms of algae clotting its pristine waters. In 2009 and 2015, massive “blooms” of algae threatened to cause severe ecological damage.

That is why lake managers now use a web-based tool called the Lake Atitlán Forecasting System. This data dashboard helps them track the health of the lake with NASA Earth science data.

“Every week, I go to the [Forecasting System page] to check on the probability of algal blooms, not just cyanobacteria but of other algae,” said Fátima Reyes. She is the head of the Department of Research and Environmental Quality for the lake’s environmental authority, the Autoridad para el Manejo Sustentable de le Cuenca del Lago de Atitlán y su Entorno (AMSCLAE).

“When the probability [of algae blooms] is high, we share with the team that we need to be attentive and be monitoring the lake. It has been a useful tool for AMSCLAE,” Reyes said.

The Lake Atitlán Forecasting System’s lead scientist is Africa Flores-Anderson, SERVIR's lead scientist on projects covering land use and land cover.

“Algae blooms in Lake Atitlán alter the ecosystem integrity by affecting the water quality and preventing oxygen and light from reaching fauna and flora living under the water surface,” said Flores. SERVIR is a joint initiative of NASA and the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID). Its mission is to support locally led environmental efforts in Asia, Africa, and Latin America with the help of NASA’s Earth science and data.

“These blooms have affected water consumption, fishing, and tourism in the area,” she said. “Though the cyanobacteria found in Lake Atitlán is not toxic, its unchecked growth may create an environment for other species of bacteria to take hold–ones that do produce toxins and could contaminate the water.”

After a 2019 algae bloom, Flores received a grant from National Geographic and Microsoft to collaborate with Lake Atitlán’s environmental authority to design the lake forecasting system. Working with her team of scientists based at the University of Alabama in Huntsville, the website gives authorities an early warning if conditions are right for another bloom.

Included in the forecasting system is information from NASA’s Global Precipitation Measurement mission (GPM). It also includes information from a weather forecasting model from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). AMSCLAE scientists validate this space-based data with water samples. This helps them understand how different conditions changed the concentration of cyanobacteria in the water. Warmer, sunnier weather could improve conditions for algae, as well as days when the water is more stagnant.

To fully understand when and where algae blooms might strike, the team also needed to keep an eye on agricultural run-off. To do this, the team also uses a freshwater stream forecasting tool. Developed by the Group on Earth Organizations (GEO)’s Global Water Sustainability (GEOGloWS) group, GEOGloWS’ Streamflow uses cloud computing to process weather information from many satellites. The computer models it creates helps AMSCLAE track how precipitation increases the flow of streams that feed into Atitlán, thus getting an idea of how much fertilizer is being washed in with it.

“Periods of high flows increase hazards for water quality because pesticides and fertilizers applied on the ground and have yet to be uptaken by the crops can be washed into the river during and after storms,” said Dr. Angélica Gutiérrez, a lead scientist with NOAA and a co-chair of GEOGloWS.

The SERVIR team hopes to replicate the success of the Lake Atitlán project to protect other area lakes. While Guatemala was one of the first countries where SERVIR operated, the Central America SERVIR hub closed in 2011. And so, the team also hopes the success of the Lake Atitlán project bolsters SERVIR’s plans to open a new hub in the region within the next year.