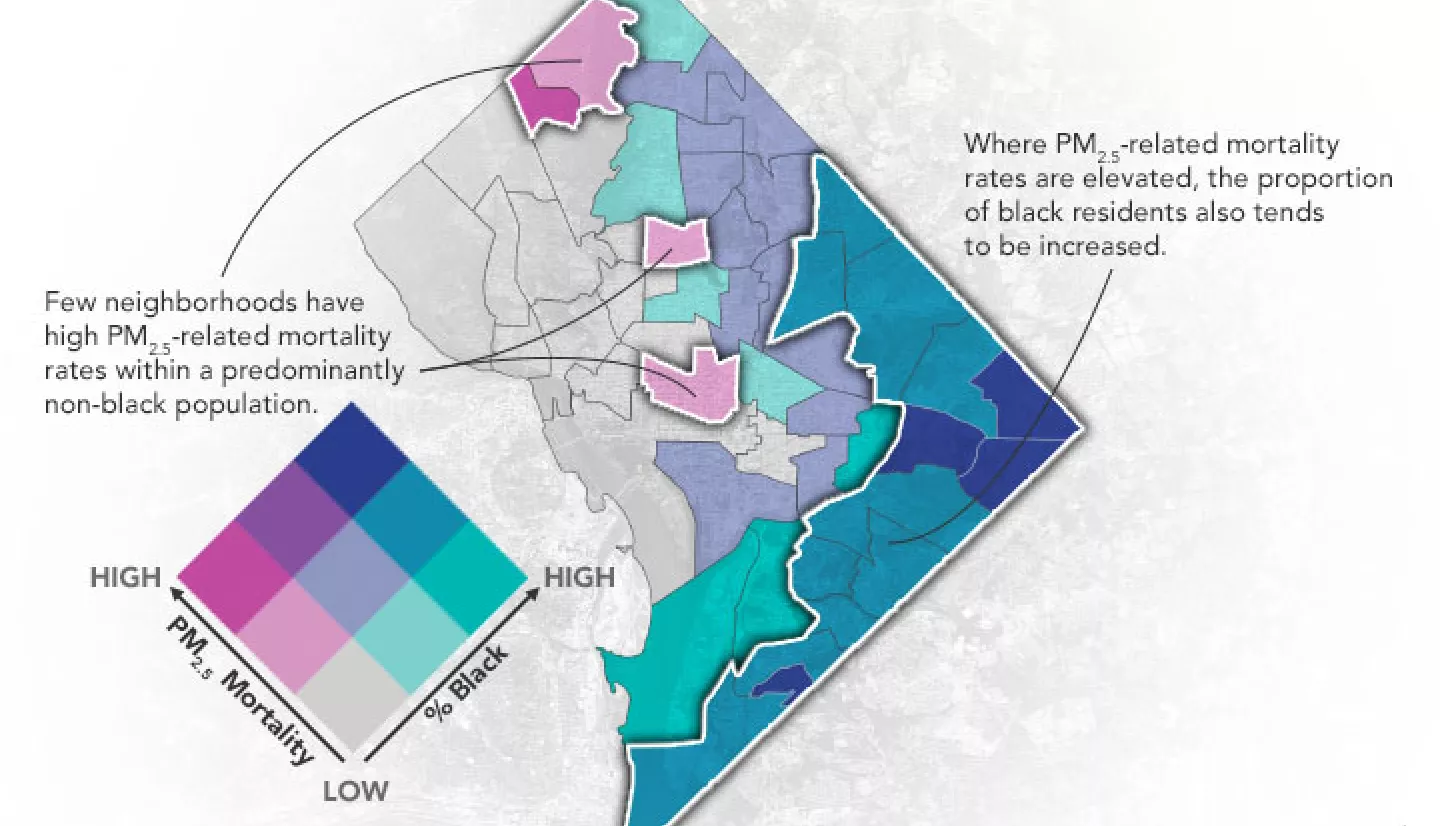

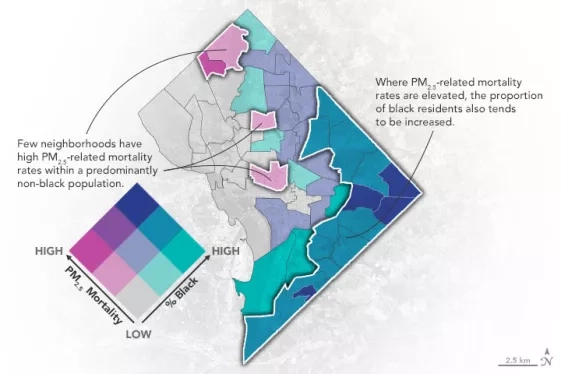

In recent decades, Washington, D.C. residents have seen major air quality improvements. One contributor is the passage of a series of clean air laws in 2000. Since then, levels of fine particle pollution (PM2.5) have declined by roughly 50%, according to a NASA-funded analysis. Although fewer DC residents are dying from PM2.5-related diseases, clean air benefits are not evenly distributed.

According to research, more people of color are facing greater exposure to air pollution and higher rates of disease. Scientists made this discovery by comparing hospital information with air pollution data.

“Exposure to PM2.5 and rates of certain health problems were highest in the southeastern, southwestern, and northeastern quadrants of the city,” said Maria Castillo. Castillo is a research associate at George Washington University. In the past, these areas have had more people of color, lower household incomes, and less education.

Castillo and her team studied aerosol observations from NASA satellites and air quality sensors on the ground. This city has only a handful of ground-based sensors. This data suggests that areas with lower incomes and higher percentages of people of color had higher PM2.5 levels.

“What’s great about the satellite data is that it has enough resolution that we can use it to fill in gaps where we don’t have data from monitoring stations,” said Kelly Crawford. Crawford is the director of the air quality division in the District’s Department of Energy & Environment and a former NASA engineer. The satellite data shows that PM2.5 levels were high in parts of the northeast, southwest, and southeast parts of the city. This contrasts with wealthier, whiter neighborhoods in the northwestern quadrant.

Other factors beyond exposure to air pollution play a role in health disparities. Examples of these factors include access to health care, smoking rates, chronic stress, and access to quality food. “There isn’t a one-to-one relationship between polluted air and poor health outcomes,” said Castillo

Understanding the nature of the problem is the first step, according to researchers. “I hope that studies like this remind decision-makers that there are ways we can address some of these longstanding inequities.”