How a NASA project is getting creative to help protect public health

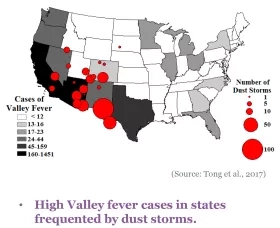

The southwestern U.S. has seen increasing dust storm frequency, which can cause low visibility for transportation, negatively impact air quality, and even carry spores of the Coccidioides fungus. Valley fever is caused by the Coccidioides fungus, which grows in dirt and fields and can cause fever, rash and coughing.

NASA researcher Daniel Tong, an associate professor at George Mason University, and his team are studying the impact of dust storms in the southwest U.S. They are supported by NASA’s Health and Air Quality (HAQ) program area to help inform local decision makers’ efforts to combat these public health threats.

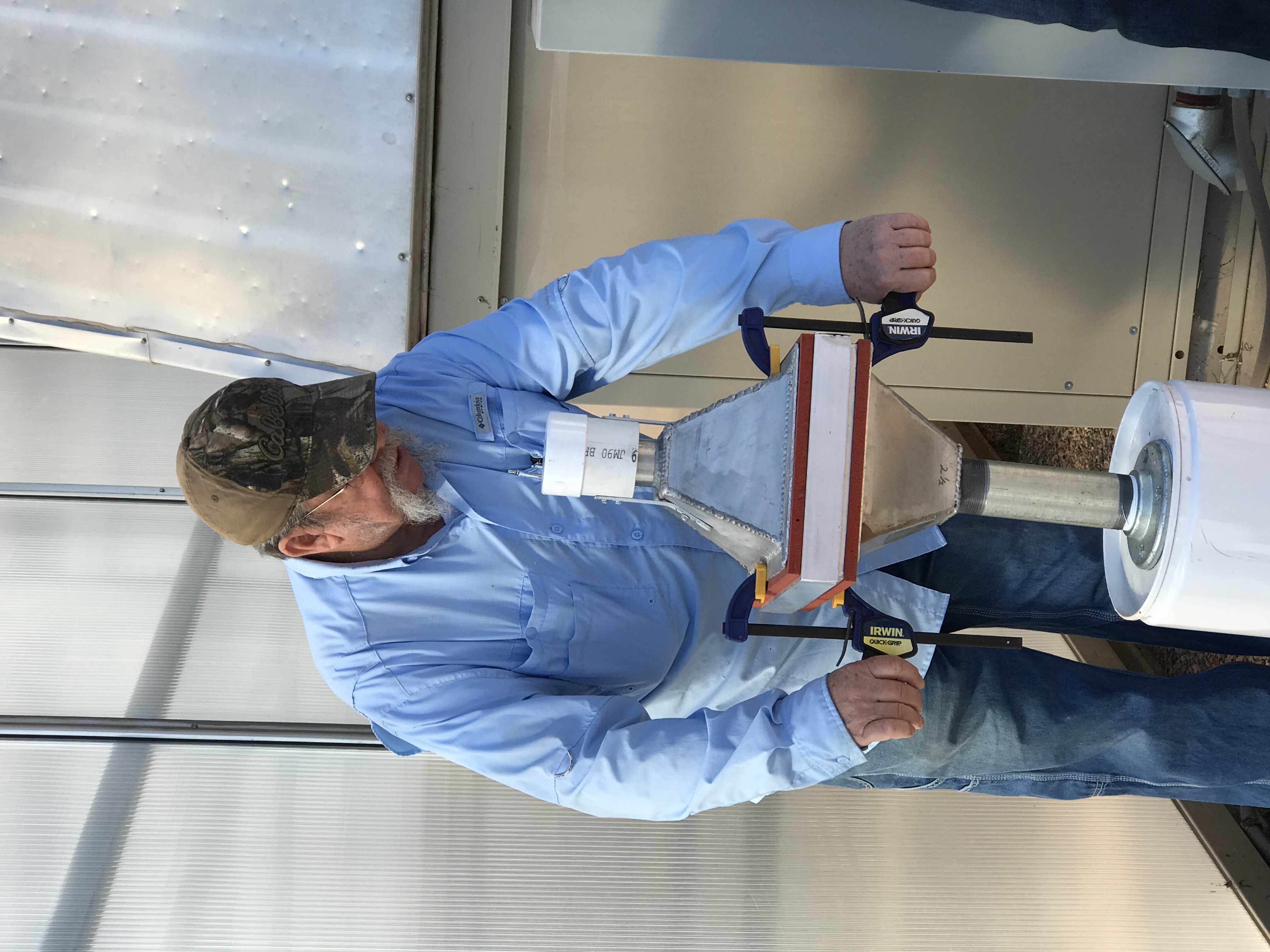

Tong’s team was looking for a way to gather many on-the-ground samples at a time. They combine this data with NASA satellite data and high-end computer modeling to enhance current forecasting and surveillance activities related to dust storms and the airborne spread of Valley fever across the southwestern states. The team realized that they could develop their own method to capture the airborne dirt – using store-bought cake pans filled with marbles. However, they found themselves with an interesting scientific challenge: how to find the right type of cake baking pan.

The team specifically needed one-piece pans to prevent dust from leaking out, as opposed to models with spring form operations and multiple parts. But “it turns out [that] cooking technology in Arizona is too advanced. The stores all had two-pieces – we need the old-fashioned type!” Tong said. They drove around two of Arizona’s largest cities in search of the elusive one-piece cake pans and bought all that they could find.

The dust catcher works as wind passes over the uneven surface of the marbles, and the interrupted flow causes the air to release the dust and spores it is carrying. Once the sediment falls through the layers of marbles to the bottom of the pan, it is protected from being picked up by wind again, stored safely until the scientists come to collect several weeks’ worth of samples at a time. With collaborations from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and George Mason University’s Institute of a Sustainable Earth for laboratory analysis, DNA is extracted from these samples, and a polymerase chain reaction test examines if there is presence of Coccidioides.

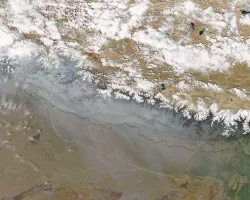

The on-the-ground measurements were combined with Earth observations from the Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) instruments aboard the NASA satellites Terra and Aqua. These satellites monitor vegetation and soil moisture, which can reveal where conditions are ripe for the growth of Coccidioides and the spread of arid dust. MODIS instruments also help track dust storms’ spread by detecting the light reflected from the tiny particles as they are swept across the country. The team also used these data to help “train” their models that assessed long-term trends of dust storms in the region.

Tong is one of the first scientists to discover the link between dust storms and Valley fever. He also learned that not only did his team need the right cake pans, they also needed the right marbles: dark in color with a rough surface.

It was Tom Gill, team member and professor of Earth, environmental and resource sciences at the University of Texas at El Paso, who suggested that the team needed dark-colored marbles. “Birds really like these shining marbles,” said Gill. “They give marbles to their friends as a gift.” So Gill made sure that the team filled the cake pan with dark colored marbles, instead of the bright ones favored by birds.

Gill is not the only one who saw the potential for this groundbreaking research to be a boon to public health. A number of scientists have offered support or technology to help ensure that Tong’s team has the data they need. Scott Van Pelt, a soil scientist from the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA), brought several low-cost dust samplers to join the field campaign. Before that, he spent several days in his welding shop in Big Spring, Texas, to make a new type of “aspirating” sampler. Van Pelt also helped the team gain access to several agricultural research stations in Arizona, where the team installed additional dust samplers. According to Van Pelt, soil-borne fungal respiratory disease has impacted his family. “Anything we can do to understand how the pathogens are aerosolized and transported will hopefully reduce the number of other families that are similarly affected,” Van Pelt said.

Tong mentioned that he greatly appreciates how the scientific and local communities are coming together to support this work. “I’ve never seen this kind of spontaneous collaboration on a single scientific project before – many scientists and organizations are lending their own expertise because they see how important this is,” said Tong.

The team is continuing to work with scientists to more accurately estimate dust emissions for regional partners in transportation (New Mexico Department of Transportation), health (Pinal County Department of Health Services), and air quality management (Pima and Pinal County, Arizona and the State of New Mexico). As a result of the team’s community engagement, local health agencies like the Pinal County Public Health Department in Arizona and community physicians are already incorporating these data to inform health and safety measures like increased testing and public education.

They have also established relationships with national and international agencies such as the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s National Weather Service, and the World Meteorological Organization. The cooperation among a network of multidisciplinary USDA Agricultural Research Service scientists from Texas and Arizona streamlined this collaboration.

More about this work to track Valley fever can be found in the NASA.gov story Dust Storms and Valley Fever in the American West.

This story is part of our Space for US collection.