The world’s second largest coral reef is in trouble, but the key to protecting it might be where you least expect it: back on shore.

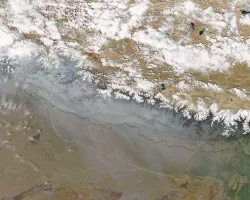

As farmland grows in Belize, more and more sediment and agricultural runoff is making its way into the country’s rivers and eventually into the sea–where it reaches the Belize Barrier Reef. Earth scientists with NASA’s SERVIR program are using satellite data to measure how those changes on land might shape the future of the country's famous marine life.

“We were collaborating with the Coastal Zone Management Authority and Institute, which is in charge of creating the national Integrated Coastal Zone Management Plan for Belize. This led to our interest in looking at the impacts of land use activities on the quality of coastal waters and of the Belize Barrier Reef,” said Vanesa Martín, a regional science associate for SERVIR.

A joint program of NASA and U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID), SERVIR collaborates with geospatial organizations in Asia, Africa, and the Americas to support decision-making for climate adaptation and natural resource management. The program is hosted at the University of Alabama in Huntsville, with the work in Belize funded in part by the Ecological Forecasting program area.

Deforestation changes the chemistry of Belize’s rivers. More farmland means more fertilizer and pesticides, and fewer trees means that excess water and nutrients are less likely to be captured on land before washing out to sea. Corals are sensitive to changes in ocean chemistry, and changes in land use can abruptly shift the amount of pollution that makes its way out to the reef. Scientists don’t yet have a clear picture of what these terrestrial changes might mean for the Belize Barrier Reef in the future.

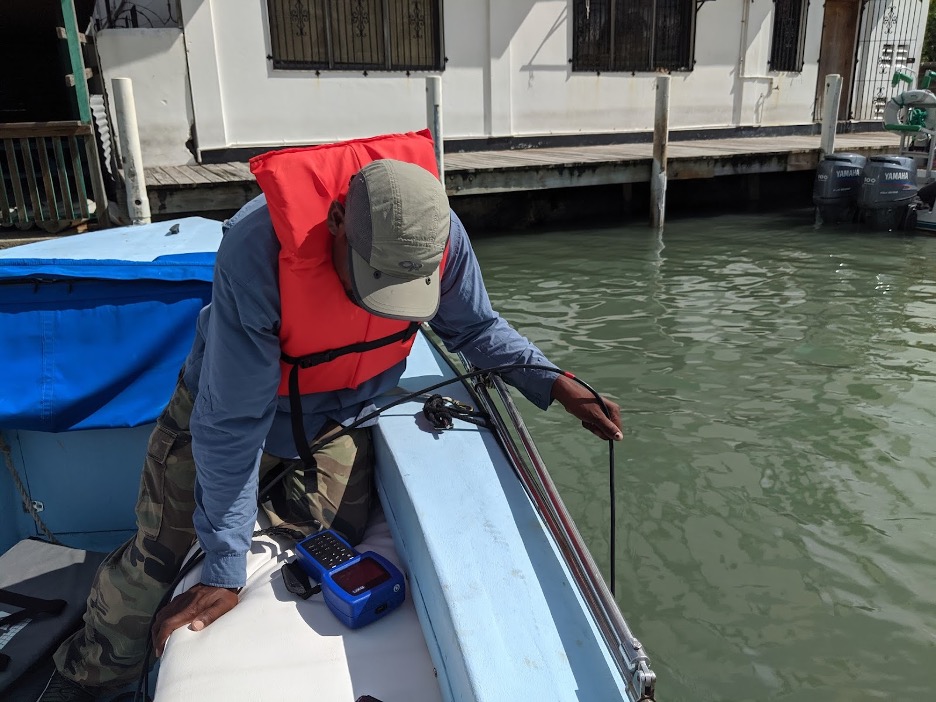

The team, led by Earth scientist Dr. Robert Griffin at the University of Alabama in Huntsville, used NASA satellite imagery to measure how Belize’s landscape changed over time, and how river conditions changed as a result. To translate changes in land cover into changes in water quality, the team used elevation, soil type, and rainfall conditions to create a system for estimating changes in surface runoff. In regions where more rainfall is washing across developed land before entering rivers, more pollutants are likely to wash out with it. If Belize’s landscape is transitioning towards land use that causes more runoff, it likely means that more pollutants will make it to the reef.

“The study produced a wide scope of deforestation and climate scenarios for stakeholders to consider in their own work,” added Martín. For a more nuanced understanding of how Belize’s landscapes are likely to shape coastal health in the future, the team estimated how different future climate change scenarios would likely shape land use in the country.

Groups like Belize’s Coastal Zone Management Authority are invested in the findings of this research because it may help them better prepare for future challenges to the country’s natural resources. Understanding how and where runoff is likely to increase in the future will be invaluable for taking steps to protect the reef. These findings will go towards supporting a coastal development plan that will help the country meet international efforts to conserve marine ecosystems. Fishing and tourism are central to Belize’s economy–if anything happens to the reef, there are likely to be ripple effects into the lives and livelihoods of the country’s citizens. Preserving the health of the reef will not only support Belize’s economy, but will also help to preserve a uniquely biodiverse ecosystem and a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

Though there are still unanswered questions about the relationship between surface runoff and coral health, the results of this study may help give scientists and local authorities better information to help protect the Belize Barrier Reef.

According to Martín, preserving the reef’s ecosystem isn’t just a local interest.

“We want to emphasize we’re not just protecting the reef for Belize, but protecting its ecological heritage for everyone.”