Dense smoke rose above a rash of wildfires in the Pampas region of Argentina in late December 2016 and early January 2017. Over the past month, roughly two dozen fires have spread across the rural landscape. The blazes were likely started by thunderstorms that followed a stretch of hotter-than-average weather, according to Clarín, a South American news site.

In mid-December 2016, news reports showed heavy smoke billowing from the undergrowth. At that point, fires south of Bahía Blanca had consumed at least 40,000 hectares (nearly 100,000 acres). Despite rain in the final days of December, a handful of hot spots persisted. By early January 2017, fires in Argentina had devoured 300,000 hectares, an area roughly 15 times larger than the city of Buenos Aires, noted Clarín.

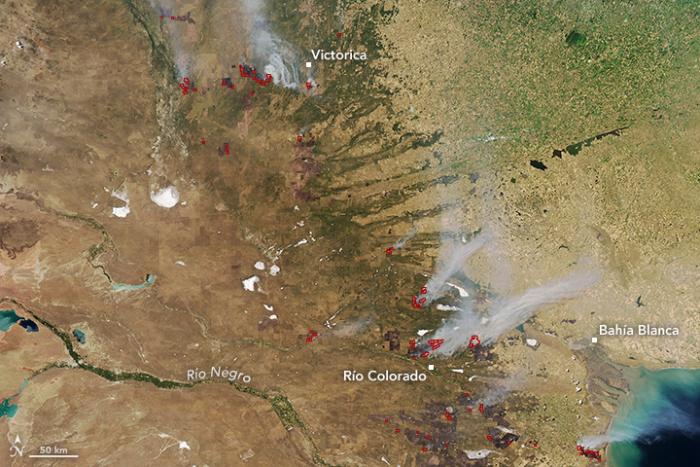

The Operational Land Imager (OLI) on the Landsat 8 satellite captured a natural-color image (above) of a smoke plume south of Río Colorado on December 29, 2016.

Severe drought during the winter and spring of 2016 in northeastern Patagonia played a large role in the current fires, said Guillermo Defossé, a professor of ecology at the National University of Patagonia San Juan Bosco and researcher for the Centro de Investigación y Extensión Forestal Andino Patagónico (CIEFAP), an organization that monitors Patagonian forests.

“While historically these ecosystems were fire prone, during the last century the number of wildfires severely declined as a consequence of a great grazing pressure—grazers consumed all fine fuels that otherwise will carry the fires—and a successful policy of fire exclusion,” Defossé wrote in an email. “This masked, in part, the fact that these ecosystems are naturally highly flammable, with a fire recurrence time of about 20–25 years. During the last 10 years, however, a very sharp decline in wool prices and continuous drought—probably due to climate change—made several ranchers to reduce the number of sheep or directly abandon the ranching activity. This abandonment increased the availability and amount of fine fuels.”

The Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) on NASA’s Aqua satellite acquired a wider view of the fires on January 1, 2017. The red outlines show dozens of hot spots, an indication of active burning. Smoke plumes stretched more than 100 kilometers (60 miles) to the west and south of Bahía Blanca; several others swirled in the skies near Victorica.

Despite their vast scale, these rural fires often receive little attention, Defossé said. That’s because they take place in areas with a low population and relatively low tourist value. “My concern now is that in general, the authorities and the general public does not pay attention,” he said.

Currently, there are active fires in La Pampa, Buenos Aires, and Río Negro provinces, according to a meteorologist with Argentina’s National Fire Management Service. The organization is still working to measure the total burned area.

References and Related Reading

- Clarín (2017, January 2) Las impactantes imágenes del incendio forestal en La Pampa. Accessed January 3, 2017.

- NASA Earth Observatory (2003, November 19) Fires in Argentina.

- Relief Web (2016, December 15) Monitoring Emergencies - Argentina - 12/15/2016: A wildfire has affected more than 40,000 hectares in the south of Bahía Blanca. Accessed January 3, 2017.

- Terra Noticias (2016, December 13) Incendio afectó 40.000 hectáreas de monte al sur de Bahía Blanca. Accessed January 4, 2017.