How NASA Earth Observations Support Food Security and Kenya’s COVID “War Room”

Kenyan farmers have been up against a “perfect storm” for the past year: floods, crop-eating locusts, and COVID-19 have all endangered the country’s food security. Because the COVID-19 pandemic limits safe social interaction, authorities have a harder time assisting farmers affected by other hazards. In turn, crop damage and reduced sales put even more pressure on communities struggling due to the pandemic. Now, Kenya is using NASA Earth observations to monitor these hazards and keep agricultural communities safe.

“During the pandemic period, the country experienced flooding in various parts of the country and the worst hit areas were around Lake Victoria and major rivers where there are low lying farming land and homesteads” said a report from Tom Dienya and Jane Kioko, heads of the Agricultural Statistics Unit in Kenya’s Ministry of Agriculture, Livestock, Fisheries, & Cooperatives (MoALFC). Dienya and Kioko also note that Kenya was already facing the worst desert locust outbreak the country has seen in 70 years. With COVID limiting the availability of casual labour that is used to tend to the fields and increasing the cost of transporting goods, agricultural communities are seriously strained.

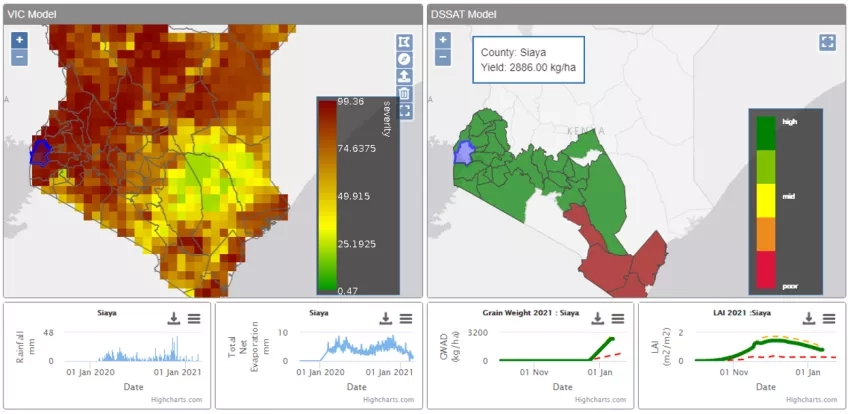

SERVIR-Eastern and Southern Africa, located at the Regional Centre for Mapping of Resources for Development (RCMRD) in Nairobi, is supporting the MoALFC’s COVID “War Room'' by providing satellite mapping of floods, locust conditions, and crop yield estimates. Sensors on NASA Earth observing satellites can monitor plant health on a regular basis by measuring changes in how green or reflective they are, and by how much infrared light bounces off. When that information is compared to crop maps and agricultural surveys, experts can quickly identify where food crops are being damaged and even estimate the economic loss.

SERVIR’s Regional Hydrologic Extremes Assessment System (RHEAS) can pair this with rainfall and agricultural data to forecast crop conditions in the near future. This information allows the MoALFC to know where government interventions may be required, even if COVID prevents personnel from being able to easily go out into the field.

“It was important for the ministry to know the location of food commodities and volumes in the event that the situation would have deteriorated to the extent of requiring state intervention,” say Dienya and Kioko. When communities experience simultaneous compounding hazards, like pandemics and food insecurity, the result is often greater vulnerability for communities and more dangers for aid workers and government personnel who must go into the field.

“In Kenya, we have seen the products filling the gap where field observations are sparse, allowing for data-driven decisions on managing agriculture and food stocks” says Lilian Ndungu, the thematic lead for Agriculture and Food Security at SERVIR-Eastern and Southern Africa. “All this has been possible due to the willingness of the government to work with us and use our products due to the relationships we have built with them over time.”

Government responses to situations like widespread crop loss or flooding typically involve the mass mobilization of aid workers, but because COVID-19 makes such deployments significantly more risky, using remote options like satellite observations becomes crucial. Thus far, conditions in Kenya have not warranted aid efforts at large scales, in part because satellite-based services are offsetting some of the need for in-person interactions. Improving the availability of Earth observations to local and national agencies minimizes the trade-off between providing aid and limiting the transmission of the virus between communities.

SERVIR is a collaboration of NASA and USAID that uses data from NASA Earth observing satellites to support sustainable resource management decisions and build geospatial capacity in developing regions.