Mary Blair knows a thing or two about how difficult it is to accurately track wild animals. For her dissertation on squirrel monkeys in Costa Rica, she created a DNA database based on hundreds of samples of poop.

"I didn’t realize how good I had it," she wrote in her online field journal. "Not only are they veritable poop machines, they also travel in groups of up to 70 monkeys, which means there’s a pretty good chance that one of them is defecating at any given moment."

Luckily for Blair and her fellow conservation biologists, there are many other methods they can use to gather accurate measures of wildlife biodiversity. With a grant from the Ecological Forecasting program area, Blair is leading a team of researchers to incorporate satellite data from NASA and other sources into this work.

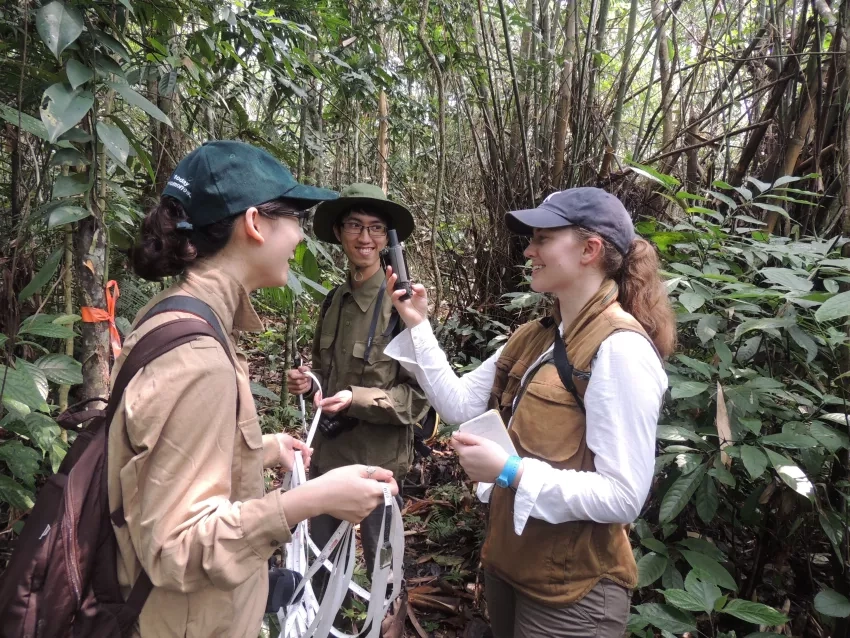

Information like forest cover and measurements of the "greenness" of plants, taken from the sky-high view of space, can be combined with current maps and climate-based models to create better estimates of an area's biodiversity. Blair and her team from the Center for Biodiversity and Conservation at the American Museum of Natural History, City College of New York – City University of New York, Pace University, University of Connecticut, and Alexander von Humboldt Institute in Colombia are working closely with the end users of these biodiversity maps in Colombia – the various scientists, government officials and conservation groups.

"It's essential to the success of the project that we are working with end user communities from the beginning. It is what I intended to do with this project, but it is also what NASA wants. NASA wants the team to build a tool that people are actually going to use," Blair said.

Blair and her colleagues in Colombia are collaborating on extending the software tool at the center of this project by adding modules to quantify biodiversity changes. Named Wallace, this web application platform will add satellite data to diverse data types already supported, including biodiversity data from online databases and user inputs, with the goal of creating species’ range maps to determine the biodiversity of a particular area, and its change over time.

Blair and her team are focused on making sure the results are accurate, and that this tool can offer long-term value for the biodiversity conservation community. "New training materials and the new expanded Wallace will level the playing field for who can create high-quality products," explained Blair.

Blair’s commitment to getting research tools into the hands of conservation practitioners can be traced to her getting to know her own family history. Her extended family include indigenous Saami reindeer herders who live in the far northern areas of Norway and Sweden.

These reindeer herders are working to maintain their traditional livelihoods under the effects of climate change near the Arctic Circle. The warming and more variable climate endangers reindeer food sources and habitat. Getting to know this part of her family was a pivotal moment for Blair – since then, she’s dedicated her career to advancing science to help understand and conserve threatened environments around the world.

One such environment is in Costa Rica, where Blair did her early research on Central American squirrel monkeys. Their natural habitat is threatened by expanding fruit plantations, tourist attractions and residential growth. Blair worked to identify where to plant trees to reconnect different groups of monkeys in close collaboration with local conservation groups to include scientific data into their work.

“I became passionate about doing research with a purpose,” Blair said. “Research with the purpose of conserving species, conserving biodiversity and helping people. Especially people who have something they already want to do to conserve the biodiversity they value and they are looking for additional knowledge or data to help make it happen.”

This experience caused her to recognize the importance of developing equitable and inclusive goals for conservation that are meaningful to local and indigenous communities, and also exposed her to a side of scientific research that continues to guide her passion for actionable conservation research today.

“I got a lot of practice in applied research and in working with the end user from the very beginning – designing a project based on a problem they had in mind, continually reporting back to them and working with them through the entire process,” Blair said. “I also presented to government ministries of the environment to improve collaboration. I didn’t understand at the time how rare and important this is, this constant checking in and communication, to affect a positive outcome for research.

"The one potential downside of co-creating tools with a user community is the potential that it may only be relevant to those users," she said. "Our goal is to ensure that the tools we create are helpful to a broad range of people by consulting more broadly with colleagues and with other conservation practitioner partners."

Blair said she's building on the lessons she learned from one of her mentors, the chief conservation scientist at the American Museum of Natural History, Eleanor Sterling.

"Eleanor had a huge influence on solidifying my thoughts about research and how inclusion, equity and diversity issues in science influence how our work is done," said Blair. "It’s not just about checking boxes – it’s more about the process and how we are forming project goals with communities and keeping them included along the way."

Blair provides the same mentoring support to others. She advises high school, graduate and post-graduate students and interns; leads career workshops; writes about her research on her social media account, and is very involved in mentoring through her local chapter of the Association for Women in Science.

"Transforming our institutions and practices to be more inclusive and equitable, for example through expanded mentoring programs, will benefit the scientific community as a whole," Blair said. "Not just by enabling all of its members to fully engage in the work that we do, but also by improving and advancing the work itself."

Also, Blair is already working on ways to adapt the Wallace software tool for another project she's developing, this time in Vietnam. This way, her team’s efforts and NASA’s investments via collaborations in Colombia can bear fruit elsewhere, and soon worldwide.

Banner Image: A Central American squirrel monkey in Costa Rica in 2008 Credit: American Museum of Natural History/Mary Blair