How SERVIR is Helping Southeast Asia Adapt to Variable Rainfall

In the United States, the agriculture sector is not immune to floods and droughts. But when these disasters hit, the system is designed to be robust enough to bounce back quickly. With an economy that depends on agriculture, many protections are in place to help farmers stay afloat, even after major disasters.

Meanwhile in Southeast Asia, increasingly variable rainfall is making life difficult for farmers. As rainfall becomes less predictable, dry seasons expand, threatening the health and quality of crops around the region. Southeast Asia depends on these crops, especially rice, which brings in billions of dollars annually worldwide. With this threat to the region’s economy, climate change has brought uncertainty to the community level. Farmers that depend on rainfall for crop yield are more negatively impacted by the less predictable conditions and are therefore more vulnerable as climate change worsens. To make matters worse, these farmers lack the same protections from which US farmers benefit. With support from organizations such as the Asian Disaster Preparedness Center, SERVIR scientists like Dr. Narendra Das are working with our regional hubs and other stakeholders on models that will better predict crop yields in the face of climate change.

“As the global population is increasing, climate change is also happening,” Das explained. “To [help with] food security, we need to have a better understanding of how much crop yield we are going to get in any given season and what is the status of the drought.”

Das is an associate professor of hydrology and remote sensing at Michigan State University and a member of SERVIR’s Applied Sciences Team. SERVIR is a joint program of NASA and the U.S. Agency for International Development. It collaborates with geospatial organizations worldwide to help communities in Asia, Africa, and Latin America address environmental challenges using data from Earth observing satellites from NASA and other space agencies. These resources are designed to help authorities make better-informed decisions about challenges like water resources and disaster management.

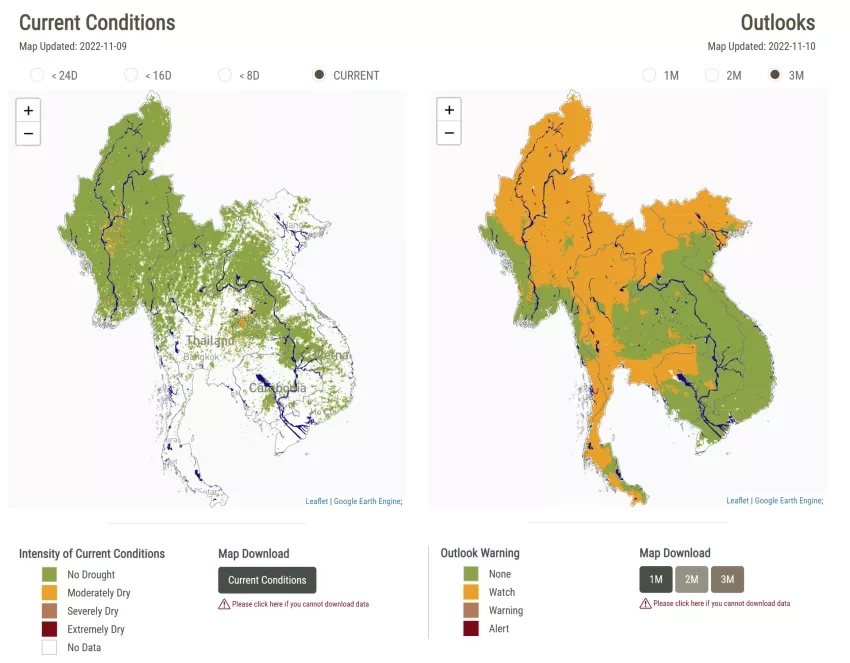

This project uses Earth observations to forecast crop yields several months in advance, giving governments in Southeast Asia time to prepare if forecasts predict a lower yield. Using a tool called the Regional Hydrologic Extremes Assessment System (RHEAS), the Mekong Drought and Crop Watch (MDCW) tool was developed to help visualize and manage the data on droughts and how they might impact crop production. RHEAS is a hydrologic modeling tool developed at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, University of Massachusetts Amherst, and Michigan State University that uses satellite imagery to automatically provide users with a current look at water resources and forecasting capabilities. The MDCW tool localizes and streamlines the acquisition of this data, automatically collecting and displaying it. This makes it more accessible to audiences without a background in remote sensing.

Das has had a lifelong interest in remote sensing but has encountered unique challenges in applying those skills to immediate needs worldwide. He talked candidly about the process of capacity building and engaging with stakeholders in new ways, including the difficulties of getting anecdotal and “on-the-ground” data from communities.

“Getting this data was very challenging,” he said. “Because sometimes the countries are very protective of these datasets, and so you have to go and convince them.” Das and his team of scientists in the US and the SERVIR-Mekong hub worked with experts in Southeast Asia to build a tool that addressed their needs directly. These experts helped to define the needs of the tool and co-developed the science behind it. Das adds that language barriers made this process even more difficult. This is where the local expertise and trust built between the SERVIR-Mekong hub and users in the region came in. Together, they were able to provide consistent reports on crop yields that shifted the way government officials in these countries made decisions.

He smiled as he added, “Now, people see the value of this project.”

And they do: multiple governmental organizations rely on Das’s work to monitor and report on crop yields in normal day-to-day operations. The Mekong River Commission and the Vietnam Academy of Water Resources are just two of the many organizations using this data to improve their water resource management. Das anticipates that as more and more communities are made aware of the power of Earth observations for monitoring drought conditions and predicting crop yield, there will be a demand for this project to be replicated. Beyond the successes in Southeast Asia, Das supports a similar project in Kenya that monitors drought conditions and maize yields. As Das moves on to other projects, SERVIR’s Mekong hub will continue supporting this project to better the lives of farmers around the region. Scientists such as Susantha Jayasinghe and Nguyen Hanh Quyen - respective theme leads for agriculture & food security and land cover & ecosystems - have worked with Das on this project and have the expertise to continue implementing it. Das is excited for the project to continue in the future, and possibly expand as more and more organizations begin to understand the extent of its capabilities for helping communities adapt to and mitigate climate change impacts.