For 14-year-old Belize-born Emil Cherrington, opportunity first came in the form of a second-hand computer.

The computer came from his aunt Carolyn Leacock-Mahung — Cherrington's childhood role model — who is currently a science teacher in Fairfax, Virginia.

"We all have that one person in our family who pushes you, and I think my aunt saw that I had a similar kind of curiosity as her," Cherrington said. "When I look back, if [I had not gotten that computer], I'm 100% certain I wouldn't have ended up working in geographic information systems (GIS), doing remote sensing or even meeting my wife. All of these fortunate things happened because I had somebody who believed in me and encouraged me."

He didn't know it then, but receiving that computer was the start of a series of lifelong opportunities for Cherrington, from traveling the globe to eventually working at NASA.

Today, Cherrington is the West Africa Regional Science Coordination Lead with the NASA Earth Applied Sciences Program Capacity Building program area's SERVIR Science Coordination Office. SERVIR is a joint development initiative between NASA and the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID). It provides local decision-makers in Asia, Africa and the Americas with the satellite-based tools, training and services they need to act on climate-sensitive issues like disasters, agriculture and food security, water management and land use.

Cherrington has been working for SERVIR for well over a decade, starting in 2005 when he received a phone call from Dan Irwin, research scientist at the NASA Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville, Alabama. Irwin is also the global program manager for SERVIR. Cherrington had recently completed his graduate degree in forest resources at the University of Washington in Seattle and was working at the Coastal Zone Management Authority & Institute, a government agency in Belize.

"If you're working in the average government agency in Belize, people from NASA don't pick up the phone and ring you very often," said Cherrington.

But Irwin had heard about Cherrington through Dan Hayes, a then Ph.D. candidate doing research with SERVIR, and the call presented yet another opportunity, one that would change the course of Cherrington's career. Irwin eventually asked Cherrington to work with the very first SERVIR hub — SERVIR-Mesoamerica — and Cherrington accepted. He went on to spend the next eight years living and working closely with Irwin in Panama City, Panama. During his time in Panama, Cherrington helped lead trainings that put Earth observations and lessons learned from NASA into the hands of local decision-makers in Central America to help them address local challenges and try to make life better for their communities.

"The SERVIR team wouldn't be the same without Emil," Irwin said. "He's been with us since the beginning, and his passion, expertise and enthusiasm for Earth Observations and capacity building have helped both empower and strengthen the many communities he's worked with all over the world."

In the midst of his career with SERVIR, another opportunity emerged, and Cherrington went back to school to get his Ph.D. He now holds a double doctorate in forest ecology from AgroParisTech in Paris, France and Technische Universität Dresden in Dresden, Germany. Cherrington also works at the University of Alabama in Huntsville while supporting the SERVIR team.

"I consider myself fortunate to be working in science," Cherrington said. "It's a privilege to be able to work with a program like SERVIR and to be a part of the Applied Sciences Program. Given the unusual times that we're living in, I think sometimes that's what gives you that extra motivation to continue laboring on when you need it. For me, looking at the things that other people are doing or saying, that provides me with inspiration as well."

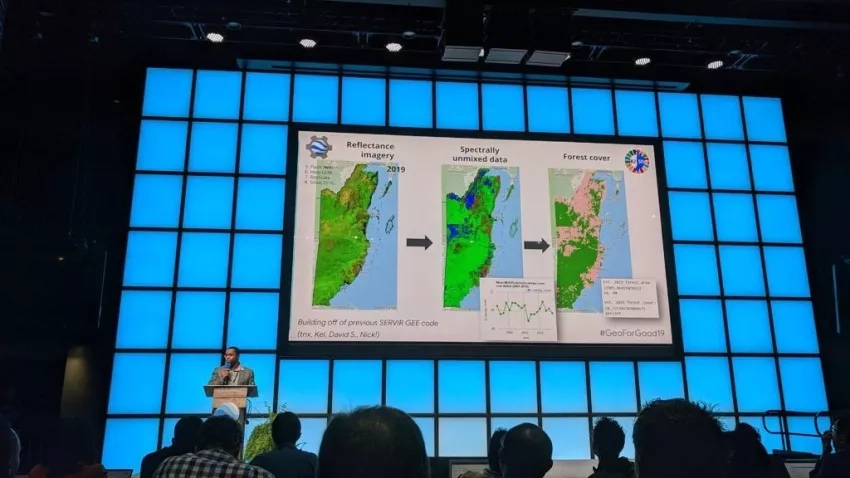

Currently, Cherrington is working on land cover mapping for an ongoing NASA-funded project called "Climate-influenced Nutrient Flows and Threats to the Biodiversity of the Belize Barrier Reef Reserve System." The team's recently published study on the project noted the decision by United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation (UNESCO) to remove the Belize Barrier Reef World Heritage Site from their "List of World Heritage in Danger." Among other factors, UNESCO had used the team's remote sensing analysis to demonstrate that the Government of Belize had, as an act of good faith, stopped mangrove clearing within the heritage site, one of the conditions needed for taking the site off UNESCO's list.

"For us, it was this really interesting example of remote sensing actually contributing to a high-level decision that has economic implications for a country," said Cherrington. In addition to the recent mangrove study, an earlier land cover study that Cherrington led was cited as a baseline in the Belize country report for the Food and Agriculture Organization's recently published Global Forest Resource Assessment 2020.

Looking back over his life and his career, Cherrington found that many opportunities were presented through the mentorship of role models around him. From his aunt Carolyn, his mother, and grandmother to his college professors to his wife (a fellow scientist) to his SERVIR colleague Emily Adams — who has led a number of global Women in Science (WiSci) STEAM camps — Cherrington has had a roster of women role models that have inspired him.

"I didn't see a whole lot of scientific role models growing up and my aunt was definitely one of those few people who was," Cherrington said. "Belize, like many other places, is a patriarchal society, and in my own life I've generally found that I've had a great deal of women role models."

Cherrington hasn't just experienced a series of opportunities over his lifetime, he also wants to help create opportunities for others and sees scientific communications as an avenue to do just that.

In talking about bridging the gap between NASA data and users, Cherrington notes the importance of weaving the human element behind the science into various types of communications, as well as the power those stories can have. Social media, he says, is a great opportunity to make those connections. Cherrington knows this firsthand from his experience running the Belize Geo Twitter account.

"I think when scientists communicate using social media or other means, they also help inspire or encourage younger folks who are also interested in science," Cherrington said. "Young people see it and realize there's so much that scientists can do. You don't have to wear a lab coat or experiment with chemicals. You can think of satellite images as puzzles and unlocking their secrets can help countries to better manage droughts or respond to crisis and disasters. And for the sake of Earth science, we need to pass that on and have young people see that this is something that they too can do and feel inspired by. It's not rocket science, as we like to say."