Meet the SERVIR Scientists Working to Protect Food Security Around the World

How will this season’s rainfall affect irrigation needs? What temperature conditions could lead to changes in the growing season—or worse—crop die-offs? NASA’s ever-growing archive of Earth data makes it possible for agriculturalists to view crops and rangelands at a grand scale—informing decision-making to manage and protect food supplies around the world. SERVIR, a joint partnership of NASA and USAID, prioritizes sustainable agriculture and increased food security as part of its broader mission within the NASA Applied Sciences Program. At the heart of this effort are five members of the SERVIR Applied Sciences Team (AST). A group of experts selected by NASA to coordinate with co-investigators at SERVIR’s regional hubs, the ASTs connect geospatial research and satellite technology to local needs. Read on to learn about the SERVIR scientists helping put agricultural information directly into the hands of the people who need it most—building new connections between space, farm, and table.

Catherine Nakalembe

Project: Earth Observation for National Agricultural Monitoring

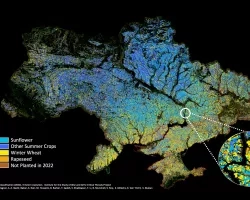

While current satellite images of farmland can be used to monitor and assess crop health across the growing season, connecting recent trends to historical data can estimate upcoming harvests. This information also helps experts pinpoint crop damaging events, like drought or locust swarms. Unfortunately, not all countries have easy access to the types of software and tools that make these analyses possible—but that’s where Dr. Catherine Nakalembe’s work comes in.

Nakalembe, an associate professor of geography at the University of Maryland and winner of the 2020 African Food Prize, works to put NASA satellite data and models into the hands of national governments across eastern Africa. By working with partners such as Kenya’s Ministry of Agriculture, Nakalembe is improving methods that leverage satellite and ground data to forecast production levels--and make these data products and models readily accessible for monitoring programs in several countries. In Kenya, these monitoring methods have already helped the Ministry of Agriculture better identify areas where crops are struggling, without needing to rely solely on in-person visits and help target aid efforts.

“Making world-class, satellite-enabled applications functional, deployable and accessible everywhere is what our team strives for,” said Nakalembe. “We want to make sure the people making decisions have access to the best-available information about our crops. So we strive to make sure the information is based on sound methods and reliable datasets.”

Frank Davenport

PROJECT: Using Earth Observations and Statistical Models to Enhance Drought, Food Security, and Agricultural Outlooks in Eastern and Southern Africa

Dr. Frank Davenport, an associate researcher at the University of California Santa Barbara Climate Hazards Center, helps east African farming communities prepare for drought and rising temperatures brought on by climate change. Davenport relies on data from climate satellites, comparing forecasts and historical conditions to estimate how harvests will vary across seasons and different climate projections. This can identify communities where drought is most likely and estimate potential harvest loss.

“There are a lot of satellite products and models out there, but translating them into actual end-of-season harvest outcomes can be difficult,” said Davenport. “We are building a set of tools and models that will help users do this by examining how well forecasts predict harvests in previous years, identifying what historical years are most similar to the current year, and then using that information to help interpret forecasts for the current season."

This information is valuable for understanding and communicating the human impact of drought to local decision-makers. It also aids partner agencies like the Famine Early Warning Systems Network (FEWSNET) to respond in the event of a severe drought or famine.

Niall Hanan

PROJECT: Range monitoring for decision support, pastoral livelihoods and food security in arid and semi-arid East and Southern Africa

Across much of the world’s arid regions, protecting food security requires monitoring rangelands. Dr. Niall Hanan, an ecologist at New Mexico State University, uses satellite imagery to investigate seasonal grazing conditions in the shrublands of eastern and southern Africa. Knowing when and where to move herds during drought is fundamental for the well-being of communities in these areas.

“Rangelands are critical resources for communities who are often economically marginalized,” said Hanan. “Our project with SERVIR builds on a long history of the Earth observation community using satellite data to monitor rangelands in Africa, but using newer satellite and computational resources that allow us to understand the spatial and temporal variability at much finer scales useful for range managers and livestock owners.”

By measuring the amount of solar radiation reflected by the landscape, Hanan approximates the amount of available vegetation for grazing. When this process is repeated throughout the year, authorities can provide maps and bulletins demonstrating seasonal grazing conditions and long-term trends in rangeland health.

Access to this data gives communities like Kenya’s Wajir County more information about current grazing conditions, as well as guidance for long-term conservation. For herders themselves, this information can be used in planning grazing routes and schedules—increasing local capacity to make the most of shifting rangeland conditions and boosting resilience in pastoral communities.

Narendra Das

PROJECT: Enhancement of the RHEAS Capabilities for Monitoring and Forecasting of Seasonal Rice Crop Productivity for the Lower Mekong Basin

Rice is the backbone of many economies in Southeast Asia’s Lower Mekong River Basin. Rice grown here feeds both local communities and people around the world, with Thailand and Vietnam among the largest rice exporting countries. However, climate change and upstream damming have complicated agricultural production along the Mekong River—creating large fluctuations in water level in a region already prone to both droughts and floods from monsoons. Knowing how these factors affect farming communities is a priority for water management organizations like the Mekong River Commission (MRC).

Dr. Narendra Das, a hydrologist at Michigan State University, works with SERVIR’s hub in the Mekong region to predict how potential seasonal climate fluctuations will affect crop harvests—particularly rice. Das is part of the team that developed the Regional Hydrological Extremes Assessment System (RHEAS), a software program designed to help experts develop reliable water resource forecasts for agricultural applications. RHEAS combines data from satellites that observe weather, soil, and vegetation conditions to provide a holistic view of a region’s water cycle. RHEAS is also built to be computationally efficient and easily adjusted to different scales and regions.

“These monitoring and forecast capabilities empower stakeholders and decision-makers to address various aspects of adaptability in agriculture, take preemptive actions for drought, provide important relief measures, and make additional resources available to farmers,” said Dr. Das. Das and the SERVIR-Mekong hub have hosted virtual RHEAS training workshops in Vietnam, helping tailor the program to local needs with real-time feedback from users in the agricultural sector and better understand risks to the region’s food supply.

Liping Di

PROJECT: Remote sensing and agro-geoinformatics based products and services for supporting agricultural and food-security decision making in Hindu-Kush Himalayan region

Farming communities in the Hindu Kush and Himalayan mountain ranges (HKH) are susceptible to a range of climate extremes—from water scarcity to flooding and landslides. These communities are also often quite remote, making it logistically difficult to perform in-person agricultural monitoring or distribute disaster aid.

“Our SERVIR project uses advanced algorithms to derive information with national coverage and field-scale details from satellite data and deliver that information through web services and citizen science tools,” said Dr. Liping Di, director of George Mason University’s Center for Spatial Information Science and Systems.

To do this, Di and SERVIR’s HKH hub developed GeoFairy, a mobile app that allows users to report conditions on-the-ground to validate observations gained from satellites that can be used by partners such as Nepal’s Ministry of Agriculture and Livestock Development (MoALD).

Building citizen science into the system not only provides a direct source of valuable community input, but also has the potential to decrease costs and the need for personnel to travel to remote farming communities in person. GeoFairy has been successfully piloted for rice planting and harvest reporting in Nepal and is now being introduced to communities in Pakistan and Bangladesh.

The Applied Sciences Team turns NASA science into real-world benefits for the farmers, ranchers, and agricultural scientists keeping food on the table. Workshops, training webinars, and investments in community geospatial skills from each AST project build opportunities for hands-on collaboration and long-term sustainability.

SERVIR’s ASTs and their co-investigators are the bridge between NASA and partner organizations around the world. Working directly with community stakeholders—from Kenya’s Department of Agriculture to the Mekong River Commission and beyond—helps make global agricultural economies and food systems more efficient and resilient to climate change.

This article is the first in a series highlighting members of the SERVIR Applied Sciences Team. Stay tuned for highlights of our ASTs working in water, land use, and weather!