The mere mention of western Montana conjures expansive landscapes and rippling rivers. This stunning aquatic system is home to many flora and fauna species. Walking along the embankment, you might be lucky to spot a river otter or American mink foraging. More likely, you might find evidence of fishing and ecotourism that helps bolster the local economy and is a mainstay for residents.

Given what an essential resource rivers are for wildlife and humans, there is widespread concern about the increasing impact of urbanization along the river’s edge. Urban run-off and other sources, e.g., wastewater, may contain contaminants such as flame-retardants, heavy metals, and pharmaceuticals. Repeated exposure and bioaccumulation of these contaminants in humans and wildlife may damage their respective neurological, endocrine, and reproductive systems.

Working Dogs for Conservation, a Montana-based non-profit organization, came up with a noninvasive solution to monitor harmful contaminants - using the noses of man’s best friend. They have trained dogs to find fecal samples of mustelid species, specifically the American mink and the river otter. Fecal samples located by the dogs are tested for contaminant residues that may have entered the mustelid food web. If contaminant residues are detected, the source of contamination may be near the point of collection. Environmentalists then have a narrower area for source identification, providing a sustainable noninvasive tool for environmental monitoring.

The dog survey method has proven highly successful in locating a large number of samples and identifying the presence of contaminants. However, finding survey sites with just the right habitat, i.e., likely to be occupied by mustelids, and with the accessibility required for safe passage by the dog-handler teams, can be incredibly time-consuming.

“It's hard to convey just how much time it takes from the ground as opposed to… having an overhead spatial view to reference. Even with a good working and visual knowledge of those key habitat components, meaning we know when we see them, it's just inherently challenging to get a sense of where most efficiently to start and prioritize surveys with dogs. We're talking about some very vast areas.”

– Dr. Ngaio Richards, Forensics and Field Specialist with Working Dogs for Conservation

In the summer and fall of 2021, the NASA DEVELOP team at Goddard Space Flight Center partnered with Working Dogs for Conservation and Dr. Mark LaGuardia at the Virginia Institute of Marine Science to provide site selection assistance. The team collected key environmental factors such as land surface temperature, precipitation, soil moisture, and elevation using NASA Earth observations from Terra Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS), Global Precipitation Measurement Integrated Multi-Satellite Retrievals for GPM (GPM IMERG), Shuttle Radar Topography Mission (SRTM), and Soil Moisture Active Passive (SMAP) respectively.

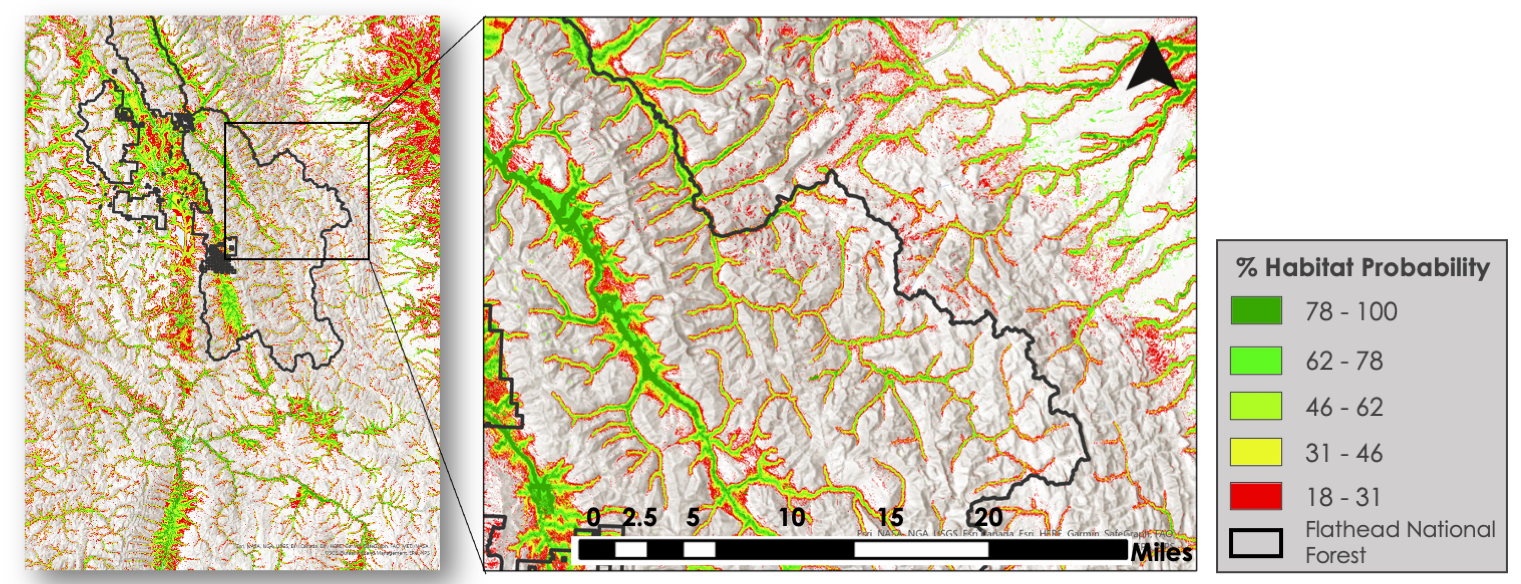

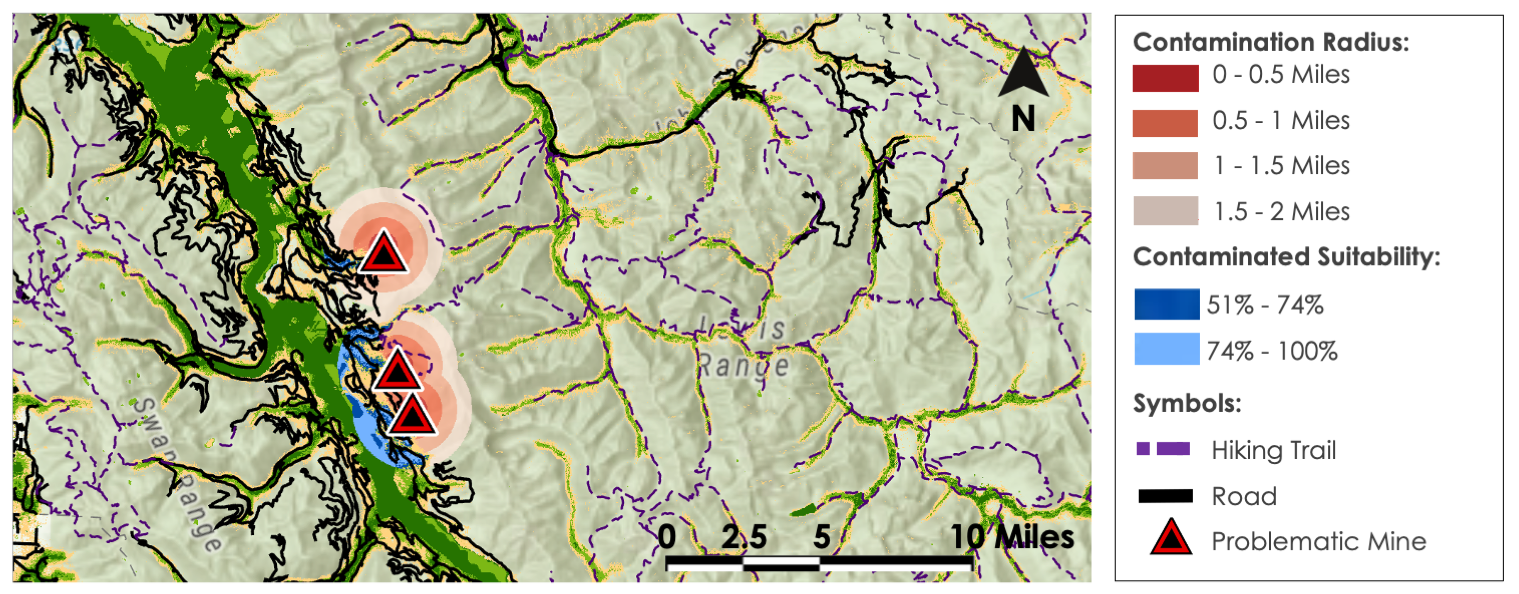

Data derived from these Earth observations and ancillary datasets were placed in the Software for Assisted Habitat Modeling to create a mustelid habitat suitability map for 2021 and a projected habitat suitability map for 2040. Alongside this analysis, the team created site accessibility maps that Working Dogs for Conservation could use to ensure that areas offering, and in the vicinity of, suitable habitats were accessible to both humans and dogs. Precipitation anomaly and topography maps also highlighted viable sampling locations based on how contaminants move through the ecosystem.

After examining the habitat suitability models, the NASA DEVELOP team found mink and otter presence is most often correlated with distance to rivers, lower elevations, and evergreen forests. The teams also found multiple sites of potential contaminants that could impact waterways and safe ways to access those sites.

With this information in hand, Working Dogs for Conservation has begun to put the habitat suitability model to the test. So far, the findings have been mixed but always very insightful. For example, some locations indicated as not ideal for mustelids have been more conducive than suggested by the model. For some locations, “these were places outside the projected habitat suitability. But when I looked at photos taken by members of the team at the site, the habitat there actually did look quite suitable for mink, otter, or both,“ said Dr. Ngaio Richards.

Other times, the model correctly identified unsuitable habitats, as verified by Michele Vasquez, a Field Lead with Working Dogs for Conservation, who stated, “most of our work is going to be on the Blackfeet reservation, but a lot of the maps kind of said there wasn't any suitable habitat there. So that's kind of an issue for us. So we had to go there anyway to look for areas, and we didn't find a whole lot.”

Dr. Ngaio Richards and Michele Vasquez are hoping to continue to use these maps in the near future as a guideline. “What we don't know is if the survey sites are gonna deliver. Or if they're gonna be viable themselves. But again, having those tools from DEVELOP does help save a lot of time … together, we're able to build something that is workable, and that can be validated. This partnership has helped us reduce some big unknowns, and that really makes our life easier in the field,” said Dr. Ngaio Richards.

In partnership with Working Dogs for Conservation, NASA DEVELOP provided multiple references to guide site selection. In turn, providing more efficient and pointed methods for water contaminant testing in the vast waterways of Western Montana. If you ever find yourself walking along the water’s edge, you might be lucky enough to see an otter or American mink, more likely a fisherman, or maybe a red-vested working dog sniffing for fecal samples around the river bend.