Stretching from the Appalachians to the Outer Banks, the Tar Heel State can boast a lot of superlatives. It was the “first in flight,” it’s home to the highest mountain east of the Mississippi River and it has the tallest brick lighthouse in the United States.

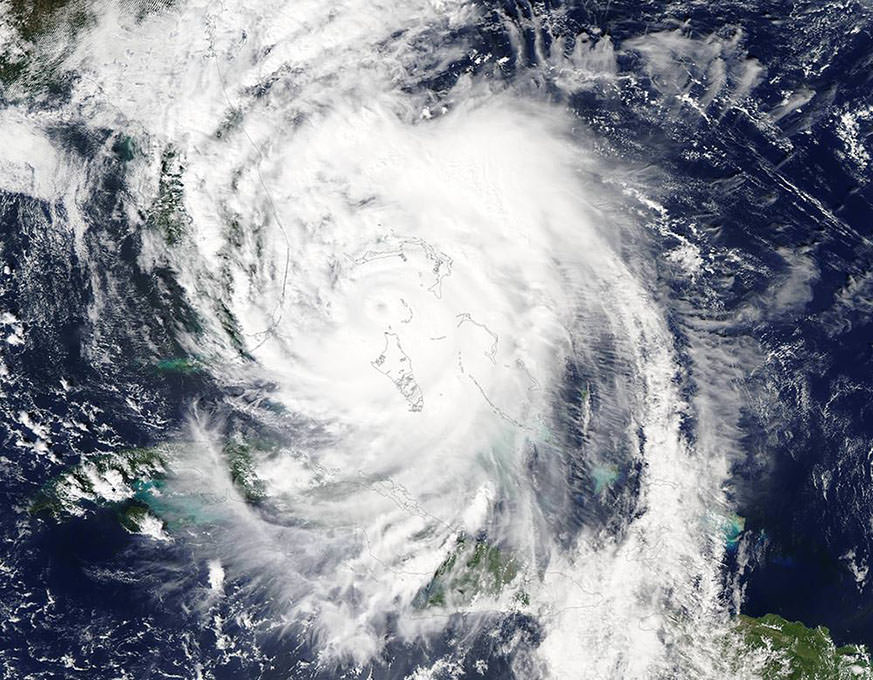

It’s also one of the most susceptible states to tropical storms and hurricanes in the United States. A tropical cyclone lashes the Atlantic coast of North Carolina about once every four years. In 2016, however, North Carolina was hit by several tropical systems. The most devastating by far was Hurricane Matthew, which left historic flooding and widespread destruction in its wake.

Well before Hurricane Matthew hit North Carolina, NASA Earth Applied Sciences Disaster Response Support Team was monitoring the storm and collaborating with other federal agencies and international partners. This coordinated effort tracked Matthew as it battered Hispaniola and Cuba before making its way toward the United States.

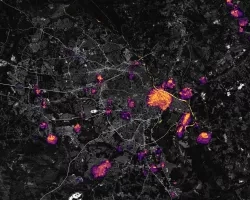

As Matthew’s effects were being felt along the Southeast coast, satellites provided crucial insights for detecting which coastal communities had lost power. For Matthew’s potential flooding impacts, the team turned to the Global Flood Monitoring System (GFMS)–a University of Maryland system sponsored by NASA’s Disasters Program. They mapped locations from northeastern Florida to North Carolina that were likely to be inundated.

The Disaster Response Support Team also assisted its partners at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) and U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) with their hurricane planning and response. By using Earth-observing systems to obtain landscape and soil moisture observations, the team identified areas of saturated soils that were prone to flash flooding—helping identify where flooding would be likely as the rainfall accumulated.

The residents of North Carolina had reason to be concerned. As the steady rain from Matthew started moving into southern parts of the state, much of the land was still swamped from heavy rainfall earlier in the week. As feared, the water quickly rose on top of saturated soils, with some locations inundated with nearly 19 inches (48 centimeters) of rain.

When Matthew’s rains finally ended, the flooding was just beginning. In many communities, the flood waters flowed east along rivers. Team members from NASA’s Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville, Alabama used multiple Earth observations to generate flood extent maps for eastern North Carolina. The team also aggregated and compared its water detections against the pre-Matthew water extent, as the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) and other response partners retrieved them through an online portal.

“NASA is helping us derive the extent of the disaster earlier … That’s one of the hardest challenges for the emergency management community early on – determining how big and bad it’s going to be.”

–Christopher Vaughan, FEMA

Christopher Vaughan, a geospatial information officer with FEMA, explained the importance of this partnership between agencies during disasters. “NASA is helping us derive the extent of the disaster earlier,” he noted. “For example, with flood extent maps, you can derive what’s inside that flooded area and estimate the levels of impact. That’s one of the hardest challenges for the emergency management community early on – determining how big and bad it’s going to be.” For Brandon Bolinski, a regional hurricane program manager with FEMA, the access to this Earth-observing data is crucial for his work as well. “By utilizing hazard layers that NASA produces, we can develop a more detailed and informed analysis of the housing and infrastructure damage in communities. FEMA leadership can then make informed decisions on placing response assets in the field.”