EARTH-OBSERVING SATELLITES ARE REDUCING OUR IMPACTS ON THREATENED MARINE MAMMALS

The largest animal ever to have lived on Earth is not a longextinct dinosaur, but a mammal that’s found throughout the world’s oceans—the blue whale. An adult can weigh up to 180 metric tons and stretch nearly 6 full-sized cars in length. Despite its massive size, this gentle giant is listed as endangered by the International Union for Conservation of Nature.

“The biggest threat to whale populations…is still humans,” said Monica DeAngelis, a marine mammal biologist with NOAA’s National Marine Fisheries Service. And the threats are numerous, she added: “Vessel collisions, climate change, habitat loss or destruction, entanglement in any kind of gear—marine debris or fishing gear.” In fact between 1988 and 2012, there were 100 documented large whale ship strikes along the California coast alone.

No ship’s crew wants to risk a whale strike during its operations, and in terms of protecting both vessel and marine mammal, the largest obstacle has been knowing where the whales are located. “The whale swims underwater most of the time and the ships don’t have a sensor that they can see it,” explained Kip Louttit, executive director of the Marine Exchange of Southern California, which oversees maritime commerce through the region. “In the same way that the ships are very conscious about the weather, they’re very conscious of the whales…and if they know where the whales are, they can avoid them.”

The practice of tagging the whales has helped both scientists and mariners track whale movements through satellite telemetry, but now a joint NASA/NOAA project is using Earth observations to predict where the whales will likely be. Led by Research Assistant Professor Helen Bailey of the University of Maryland Center for Environmental Science, the project integrates the tagging database with NASA satellite information to generate an online tool called WhaleWatch.

“We have tracking data from 1993 to 2009 that was collected by Bruce Mate and his team at Oregon State University,” said Bailey. “[With WhaleWatch] we are combining the satellite telemetry data for the whales with satellite-derived environmental data to understand not just where are the whales going, but why are they going there.”

That environmental data includes sea-surface height, sea-surface temperature, chlorophyll concentration, and water depth. These factors help characterize habitats the blue whales favor or travel through during different times of their migration. With this information, the team is able to determine suitable locations for the whales, and then predict where they are moving along the California Current System, from Washington State southward to Baja California.

The benefit of the satellite data is that it fills the gaps in the telemetry data—providing new insights into blue whale migration and behavior. During the project’s research, the team found that “the most important variables were sea-surface temperature, which helped to explain the seasonal migration…chlorophyll concentration, which was related to the abundance of food, and…ocean winds,” Bailey remarked. The winds were important because they produced the upwelling that supports the whales’ food source—krill. In addition, information on seabed slope determines where the krill aggregate.

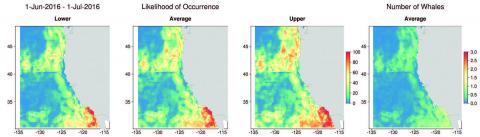

With this combination of multiple data sources, the project team was able to create maps of standardized daily blue whale locations as well as habitat-based models of population density and probability of occurrence—a blue whale forecast, so to speak.

Marking the culmination of this project, these forecast model maps are now online and publicly available on NOAA’s website, so the question of knowing where the whales are located and headed can be solved by the click of a mouse. In fact, with its success with the blue whale, this approach is now being used for other species.

“The bottom line is, this is the best available science,” DeAngelis noted. “We are now able to use that information to give whales a voice, so that humans can change their behavior to reduce the threat to whales.”

Helen Bailey leads this project.

To check out WhaleWatch, visit http://www.westcoast.fisheries.noaa.gov/whalewatch/index.html