Arkansas lives up to its nickname of The Natural State, with three national forests covering 2.9 million acres, seven national parks, scenic mountains and plains, and dozens of rivers bordering and crossing the state, including the mighty Mississippi.

But with all those rivers, flooding is a recurring natural hazard. For those providing relief and other emergency services to flooded areas, timely NASA Earth observations help determine the scope of the disaster.

“NASA is helping us derive the extent of the disaster earlier,” said Christopher Vaughan, a geospatial information officer with the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA). “That’s one of the hardest challenges for the emergency management community early on – determining how big and bad it’s going to be.”

Nestled in Northeast Arkansas, Randolph County has five major rivers running through it – the most of any county in Arkansas. Its county seat is Pocahontas, which sits along the banks of the Black River. The community has seen several major floods just in the last decade.

“NASA provides data, subject matter experts and satellite imagery when and where we can.”

–Andrew Molthan, NASA Marshall Space Flight Center

“The flooding in May 2017 was the result of a 'perfect storm' that distressed three of our rivers and two tributaries that all eventually needed to travel under the Black River Bridge, near the center of Pocahontas,” said Randolph County Judge and lifelong resident David Jansen. “Flood stage for the Black River at the bridge in Pocahontas is 17 feet [5.18 meters]. [During the 2017 flood,] it crested at 28.95 feet [8.82 meters].”

Once the river hits the critical flood mark of 26.5 feet (8.08 meters), its waters start crossing over Highway 67, effectively bringing Pocahontas to a halt. “This causes the main artery to the county seat to be shut down and affects the main hub for retail and commerce activity in our area,” Jansen explained.

Flooding from Randolph County’s Current River during the same event cut off the municipalities of Biggers and Reyno. “The roadways to these towns were under water,” Jansen said. “At one point, the only access to the area was by helicopter, which was used for medical emergencies.”

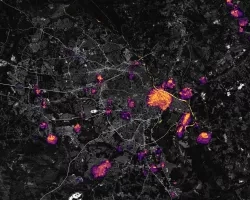

During domestic flooding events like these, NASA uses Earth-observing satellites to gain insight on the disaster to share with other federal agencies, including the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS), the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) and, especially, FEMA.

“During disasters, FEMA will give us guidance on what it needs in terms of products and information, and NASA’s Earth Applied Sciences Disasters Program will then see what we can provide,” said Andrew Molthan, a research meteorologist at NASA’s Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville, Alabama. “NASA provides data, subject matter experts and satellite imagery when and where we can.”

For the 2017 Pocahontas flooding in particular, NASA provided FEMA with flood maps derived from satellite images, along with supplementary rainfall estimates and other products.

As the flooding continued across Arkansas, NASA and FEMA used Earth-observing data to verify FEMA’s flood mapping and modeling forecasts – including locations where the flooding forecasts didn’t pan out as expected. NASA and FEMA took the lessons learned in Arkansas and applied them extensively during the devastating 2017 hurricane season that came just a few months later.

In the flood’s aftermath, Arkansas National Guard Specialist Stephen Wright provided a sobering statistic: “According to the University of Arkansas System Division of Agriculture, water engulfed more than 977,800 acres [3,957 square kilometers] of cropland in 21 out of 75 Arkansas counties, causing over $175 million in losses of farmland alone – not including residential or business losses.”

The disaster had a silver lining, however. Despite 50 water rescues, there were no casualties in Randolph County. “Our number-one priority in any natural or man-made emergency is no loss of life,” Jansen said. “We achieved that goal during the 2017 flood.”

This story is part of our Space for U.S. collection. To learn how NASA data are being used in your state, please visit nasa.gov/spaceforus.