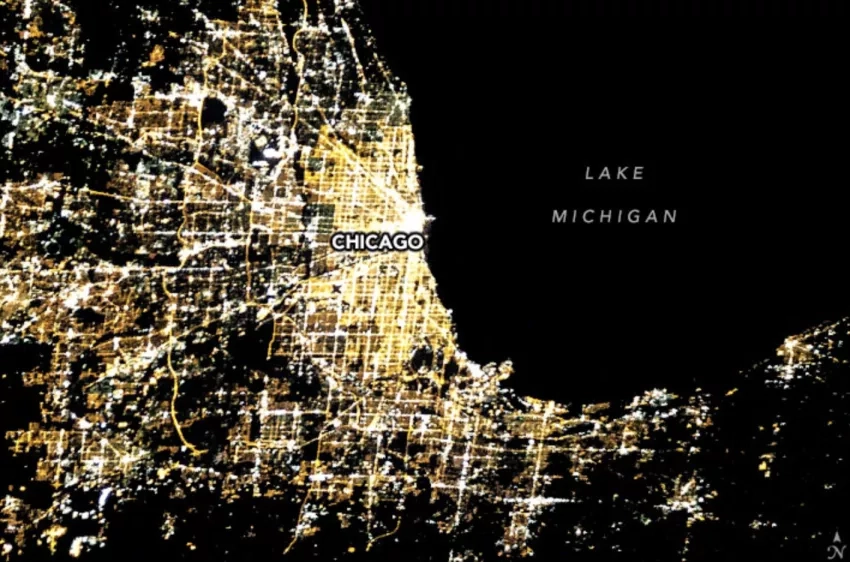

When night falls, urban areas like Chicago twinkle with artificial lights, bright enough to be seen by astronauts in space. In fact, astronauts’ photos of the lit-up city have helped researchers understand the effects of light pollution and document how it can disrupt the movement patterns of nocturnal animals.

In a 2019 study, biology researchers from Northeastern Illinois University found that Chicago’s animals like coyotes, possums, raccoons, rats, and skunks became less active as levels of artificial lighting increased at night. Significant changes in animal behavior were observed starting around 6 lux, a unit to measure lighting. For comparison, 6 lux is slightly dimmer than Earth’s surface at twilight, while kitchen lighting is typically around 500 lux.

To map light pollution across the Chicago area, lead author Aaron Schirmer and his colleagues measured light intensity levels around the city using handheld light meters. These ground measurements were combined with nighttime photographs of the city captured by astronauts aboard the International Space Station.

The researchers then recreated the city’s artificial lighting conditions in a lab to conduct a series of experiments with mice. Schirmer and his colleagues watched the activity level of the mice decrease as the animals were gradually exposed to light levels mimicking those typical of Chicago.

Observations of wildlife around the city helped confirm these results. The Lincoln Park Zoo has collected more than 1 million photos of Chicago-area wildlife over the past decade with camera traps. Through an analysis of these images, the researchers found that Chicago’s nocturnal species moved less when exposed to high levels of city light. Opossums, raccoons, skunks, and other animals were 19.6 percent more active in darker locations than in brighter areas.

Photos from the Space Station were again used to help map the light-polluted areas of Chicago where wildlife is most likely to be affected. About 36 percent of the city’s green space is regularly above 6 lux, the researchers found.

“We want this study to raise awareness of the impact of electric light pollution on wildlife,” said Schirmer. “From an urban planning perspective, it is important to think about ways in which nighttime light impacts animals and to find creative solutions that work for people and the wildlife.”

More information can be found at the Earth Observatory story, Night Lights Can Disrupt Wildlife.

This story is part of our Space for U.S. collection.