NASA Harvest scientists joined Earth Science Division Leadership in a 2022 Farm Tour Across Nebraska and Kansas

NASA scientists toured farms across the US Corn Belt in 2022 as part of the Agency’s effort to better link with farmers and agricultural producers, and to improve how NASA shares and expands its data archives. Organized under the leadership of the Director of NASA’s Earth Science Division, Dr. Karen St. Germain, several NASA scientists from across the country who use satellite data to support agriculture and water resources management made stopped at farms across Nebraska and Kansas producing corn, soybean, wheat, sorghum, and cattle, among others. Scientists on the trip included Dr. Brad Doorn, program manager of NASA’s Agriculture and Water Resources program areas, and Dr. Alyssa Whitcraft, deputy director of NASA Harvest and Director of the Harvest Initiative on Sustainable and Regenerative Agriculture, as well as Dr. Chris Hain (NASA Marshall) Dr. Forrest Melton (NASA Ames). Hain is the principle investigator for NASA’s Short-term Prediction Research and Transition Center (SPORT). Melton is the program scientist for the water resource management tool OpenET.

The tour provided a unique opportunity for NASA to come “down to Earth” and hear from producers and extension agents across the region who are seeking ways to improve their operations while battling increasingly common environmental hardships like drought, temperature extremes, and soil degradation. NASA scientists asked questions about these challenges and their information needs, and in turn shared the different kinds of Earth observation data NASA is collecting and how it is being applied to support on-farm decision making.

NASA’s Focus on Earth

Variations in temperature, precipitation, and the health of soil have major impacts on agricultural productivity, and the impacts of climate change stand to increase these variations and their extremes. The challenge before US producers is to implement management approaches that reduce risk and increase resilience to climate change and extreme weather events, while continuing to be the world’s largest agricultural commodities exporter.

Monitoring these environmental conditions allows us to better estimate crop yields which in turn informs commodity markets and policymakers ahead of price shocks and food insecurity. Traditional methods of monitoring agricultural land use and productivity, for example through “windshield” surveys, are often labor intensive and require extrapolation over large areas, without much opportunity for repeated measurement.

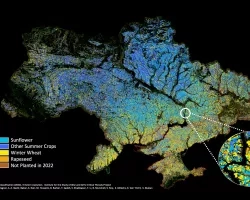

Advances in GPS, satellite-based Earth observation systems, and artificial intelligence/machine learning have enabled scientists to develop measuring techniques that allow markets, governments, and farmers to remotely monitor cropland from sub-field to global scales. Unknown to many, NASA, in addition to its space exploration, spends much of its time studying Earth. “The planet that we study the most is our home planet,” St. Germain told farmers during a visit to Hunnicutt Farms in Giltner, NE.

The agency has multiple satellites pointed downward towards Earth, mapping everything from temperature and precipitation to vegetation health and water levels in the soil. These decades-spanning data archives have been made available to the public in a variety of online platforms, including Google Earth Engine, the U.S. Geological Survey’s Earth Explorer, and the NASA Harvest Global Agricultural Monitoring (GLAM) system.

Until somewhat recently, limitations in satellite data and its availability or discoverability have limited its application for on-farm decision making and agriculture monitoring. A new generation of airborne and spaceborne instruments launched by NASA, its partners at other space agencies, and private space and aviation companies have opened the floodgates to new opportunities to bring the value of remote sensing to producers across the globe.

This tour’s primary goal was to listen and learn from US producers on the ground, many of whom are already experimenting with data and tools from different airborne and spaceborne instruments to guide their on-farm decision making. But as became clear on the tour, many producers lack confidence in what these remote measurement tools are telling them, and have remaining information needs that satellites might have potential to meet.

The tour provided the NASA team with the opportunity to spread awareness of the unparalleled quality of its missions and their rich data archives - such as Landsat, which just reached its 50th anniversary of operation - and to better understand how they might get NASA data, science, and tools into the hands of these users. These discussions are an important way for NASA to identify priorities for future missions, investigations, and end-user engagement.

Speaking with the Kansa State Research and Extension office, Doorn explained, “We want to learn the decisions [farmers are] facing, the technologies they’re working with…so that we can get better acclimated to those challenges. We then reach back to NASA and explain the possibilities. It could be that it’s a future (space) mission, 10 years down the road. It could be something that we’ve already developed; we just need to say, ‘hey what’s been done over here, we need to bring over here…”

But as satellite-based solutions for agriculture proliferate, farmers may be struggling to ingest or choose their information source. Nebraska farmer Zach Hunnicutt noted, “Data overload is always a concern, you can get more and more information thrown at you.”

NASA’s authoritative voice can bring clarity to the field. “Agricultural producers and industry need to understand that they have an agricultural program in the nation’s space agency,” added Doorn, echoing the tour’s objective to understand how to get the right data and information into farmers’ hands.

Building Partnerships to Bolster Agricultural Resiliency

Satellite data play a central role in market- and policy-driven needs for monitoring, measuring, reporting, and verifying the state of agricultural sustainability and emissions from farm to global levels. Several growers disclosed that the emergence of carbon markets and incentive programs intrigued but perplexed them. They expressed a deep motivation to leave a legacy of soil health and profitability to the next generation to take over their farms but had practical concerns about whether and how those objectives align with the push to “farm carbon.”

NASA Harvest’s Whitcraft herself has the same question - how can we simultaneously continue to increase production, while supporting land, water, atmosphere, and human health, and while continuing to provide livelihoods for US farmers, ranchers, and the other 1 billion agricultural workers worldwide? And has also wondered how we in science and at NASA can use this top-down view in a way that provides value to farmers and respects their autonomy and privacy?

This led Whitcraft to launch the Harvest Sustainable and Regenerative Agriculture (SARA) Initiative, which builds upon NASA Harvest’s world-renown science and relationships with top multi-disciplinary researchers to advance transparent, validated methods and knowledge about adoption and impacts of agriculture management techniques on crop yield, farm profitability, soil health, GHG emissions and reductions, water quality, and air quality. Harvest SARA has begun convening agriculture stakeholders, top scientists, practitioners, and leading voices in agriculture data policy from public and private sectors to advance the underpinning science of using Earth observations for agricultural decisions and to bring clarity to how agriculture is adapting and can adapt to global change. The initiative is currently working on a number of projects including nutrient management, soil moisture monitoring, and conservation tillage, and is shortly launching an initiative to improve accounting of net carbon exchange in agricultural systems.

Having grown up working in her family winery, Whitcraft recognized the environmental and economic concerns that many of the farmers brought to the tour’s stops. “Nearly everyone I have ever met who works the land knows that things are changing - the length of seasons, the severity and persistence of drought, the intensity of storms, not to mention what conflict and supply chain disruptions bring to the table - and for a lot of producers, the net effect has been a more difficult, costlier operation. We have seen producers in the US, including on this trip, doing amazingly innovative things to adapt their operations, and increase yield and profitability while they do it,” Whitcraft said. “From talking to the farmers we met on this tour, it is clear to me that we can do a lot in our little corner of science to support them.”

Monitoring Cropland From Space

These changing conditions are what motivate Whitcraft to use remote sensing to develop more effective agricultural monitoring models.

“Studying the fields from space has a number of advantages. Satellites are passing over us all the time, and so with them we can monitor progress in near real time, which makes it easier to respond sooner. And satellites collect information about the crops that we can’t see with our eyes, be it water stress, or nutrient stress, pest pressure, or forecasts of yield across a field or region,” Whitcraft said.

“Nothing replaces place-based knowledge and experience when it comes to farm management, but satellite data and tools like those from NASA can help provide a steady stream of low to no-cost information that can help farmers respond to current season challenges and anticipate what is coming down the pipeline.”

Scientists from the region also attended parts of the tour, including Dr. Deann Presley, a soil scientist who studies how cover crops impact soil health and crop productivity. Presley is a partner in the national Precision Sustainable Agriculture Network led by NASA Harvest collaborator Dr. Steven Mirsky of the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Agricultural Research Service (USDA ARS). Presley sees an opportunity for satellite data to complement her studies and her service to Kansas farmers through K-State Extension.

“I just think it’s fantastic that they’re willing to listen and have that conversation with farmers,” Presley said. “[NASA] are the ones taking these measurements of Earth; they’re the ones helping with drought prediction and looking at food security around the globe. But they want to take it further; they want to learn what kinds of tools and products can be useful to farmers.”

A Look Ahead

Farmer Derek Klingenberg, a 3rd generation Kansas farmer with over 150,000 subscribers to his YouTube channel where he shares comedic and informative videos of his farm life, was similarly enthusiastic about NASA’s visit. “I had an absolute blast with NASA,” he said, and then looked up at outer space to add, “and you guys can come visit me whenever you want!”

And that is just what NASA and NASA Harvest plan to do: get down to Earth and deeper into the research and applications to support farmers in Nebraska, Kansas, across the US, and worldwide.