Moore, Oklahoma, a city of 60,000 just south of Oklahoma City, is a shining example of Sooner State resiliency. On one particularly devastating afternoon in May 2013, an extremely large and violent tornado brought widespread destruction and casualties right through the heart of Moore. Its winds were estimated at more than 200 miles per hour (321 kilometers per hour) as the twister cut its mile-wide path across 17 miles (27 kilometers) of Oklahoma.

Immediately following the tornado, a team from NASA’s Short-term Prediction Research and Transition (SPoRT) Center jumped into action. NASA’s SPoRT Center analyzes the practical uses of Earth observations for meteorology, and transitions them to the weather community for real-world applications. For this storm, SPoRT tapped into a fleet of NASA satellites and sensors – as well as Earth-observing data from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) and other partners – to determine the extent of the tornado’s rampage.

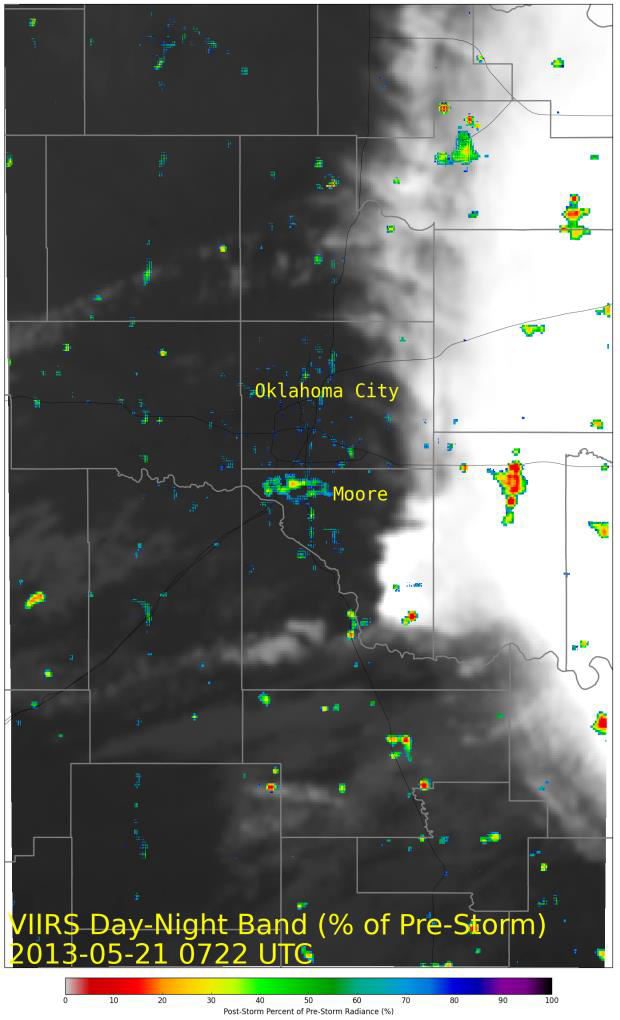

First, the SPoRT team used satellites to locate areas affected by power outages – an indication of infrastructure damage. During major disasters power outages can be long term, impacting wellness, safety and recovery efforts.

“We looked for a [satellite] image immediately prior to the tornado event and then obtained a cloud-free scene the following evening,” noted Andrew Molthan, a research meteorologist with SPoRT. “Severe storms that occurred in the afternoon had shifted just far enough to the east so that cloud cover had moved out of the area, allowing for a difference between pre- and post-event light emissions.”

With those images, SPoRT identified locations with outages and shared that information with response partners to guide their recovery efforts.

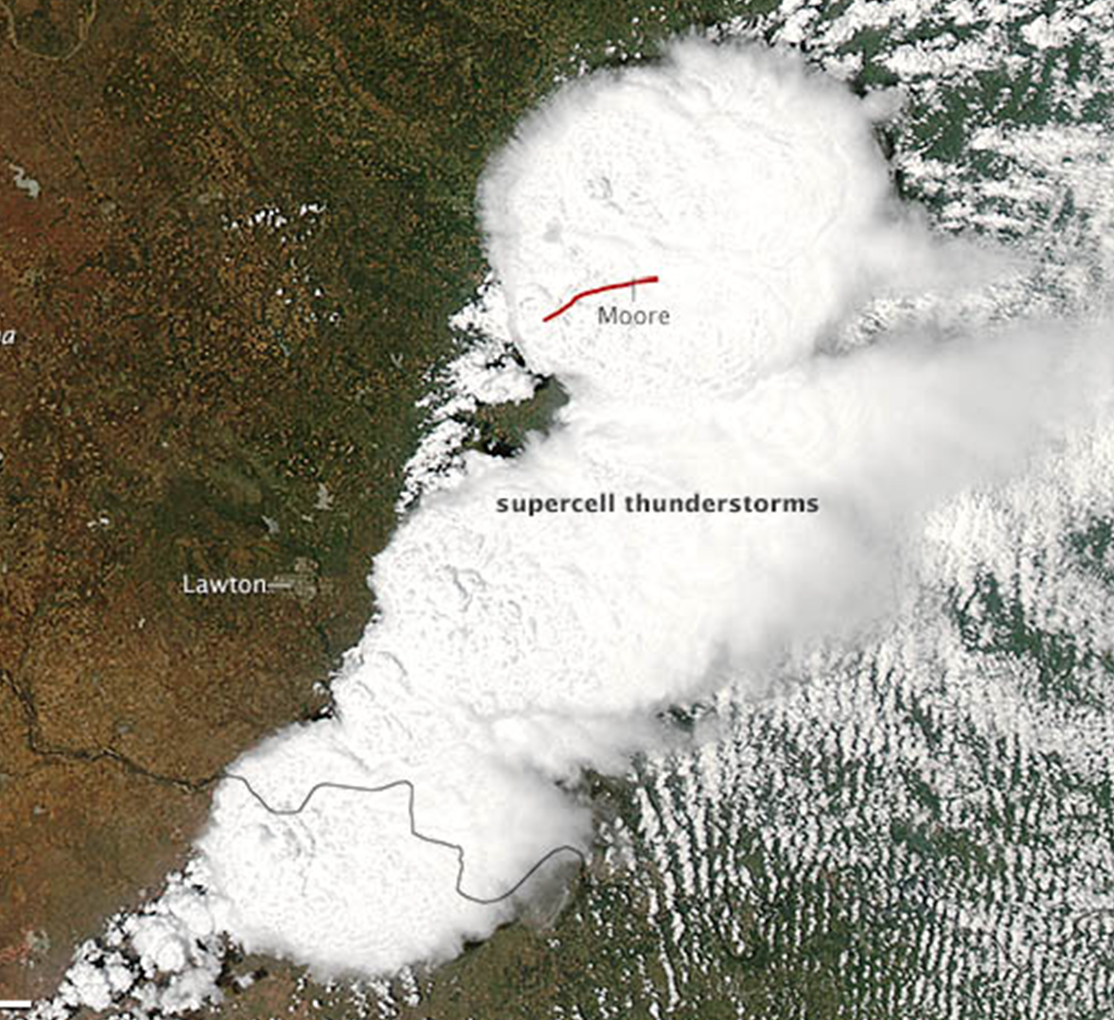

The SPoRT team also worked with partners at NOAA’s National Severe Storms Laboratory to analyze lightning data and review the amount and frequency of lightning associated with the tornado’s “parent” thunderstorm. In a post-event review, they detected three “lightning jumps” from the thunderstorm before the Moore tornado. Each jump signaled when the storm intensified.

“Scientists at NASA’s Marshall [Space Flight Center] and the University of Alabama in Huntsville, along with other partners, have documented that there are often surges in the amount of total lightning that accompany the intensification of the thunderstorm updraft,” explained Molthan. “Observing these ‘jumps’ in lightning indicates an increase in intensity of the thunderstorm, and often precedes the occurrence of some type of severe weather by around 20 minutes.” With this information, partners at NOAA’s National Weather Service (NWS) can more accurately predict where and when a thunderstorm will become severe, as well as issue more timely and detailed warnings to the public.

As Moore continued to pick up the pieces and rebuild in the weeks following the tornado, SPoRT acquired more NASA satellite imagery to assist with the ongoing damage assessments.

“Satellite imagery can help to extend the mapping of a damage track into areas that weren’t accessible to the surveyors and provide additional information about the width of the track.”

–Andrew Molthan, NASA’s Short-term Prediction Research and Transition Center

Following a severe weather outbreak and suspected or known tornado, NWS meteorologists are tasked with completing a detailed storm survey to map the extent of the damage and changes in the tornado’s intensity along the path. Satellite imagery can help to refine the position of a track, particularly for a storm that may have been surveyed by multiple teams.

With the imagery, surveyors can more accurately report the length of the tornado’s track and its estimated wind speeds. An accurate position of the track is important to inform the emergency response and insurance communities.

Molthan added that SPoRT will continue to explore opportunities that improve the use of NASA, NOAA, and commercial partner remote-sensing in support of severe weather and other damage assessments. “[We will] also look to partner with others in the community and help to integrate their research outcomes for benefit to the disaster-response community.”