More than just a grand estuary, the 782-square mile (2,030 square kilometer) Delaware Bay is where freshwater from the Delaware River and saltwater from the Atlantic Ocean mix, creating both a vital Delaware resource and a home to an endangered species, the Atlantic sturgeon. NASA data is used in a mobile app that tracks and forecasts adult sturgeon movements so that fishers can avoid dangerous and costly encounters with the mighty fish.

“The Delaware River Estuary is incredibly important to the ecology and economy of Delaware,” said Ed Hale, a biometrician at the Delaware Department of Natural Resources and Environmental Control (DNREC). “Our fisheries resources — for managed species — are worth over $100 million per year. Ecologically, the estuary hosts multiple life-history stages of critically endangered Atlantic sturgeon.”

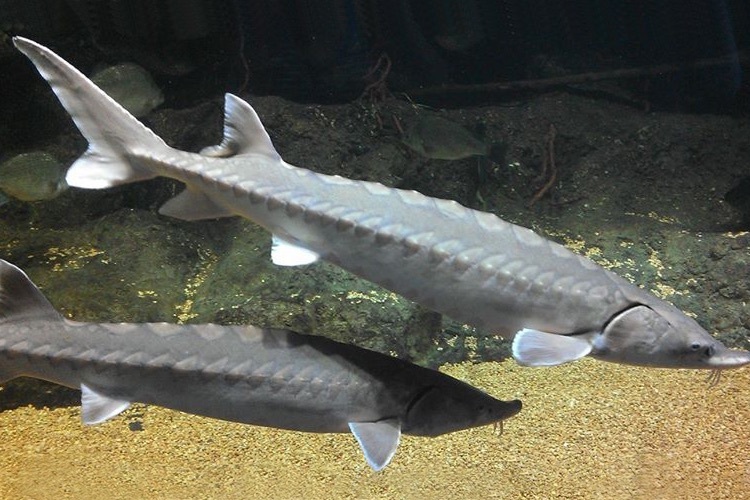

Covered with sharp, bony plates, the Atlantic sturgeon is an impressive fish. Adults can grow up to 14 feet (4 meters) long and weigh 800 pounds (363 kilograms), and they have few natural predators other than sharks and people. Adult Atlantic sturgeon enter the Delaware Bay from the ocean and remain in its fertile-friendly waters until environmental cues signal that it’s time to release their eggs.

“At that time, they move up river and spawn in the mid-to-late spring,” explained Ian Park, a fisheries biologist with DNREC. “The adults then return to the ocean while the offspring remain in the river and estuary for the first few years of their life.”

By the 20th century, however, human activity brought the sturgeon to the brink of extinction in American waters. After a slight rebound, the Atlantic sturgeon was finally listed by the Endangered Species Act in 2012, which included a ban on all East Coast fishing. Still, accidents happen.

“Because these species are large-scale coastal migrators — and use river systems for spawning — many [human] activities potentially interact with this species, including: shipping, dredging, commercial fishing and development of offshore wind-power farms,” noted Matthew Oliver, an associate professor at the University of Delaware.

Commercial fisheries in the bay are more than happy to avoid sturgeon altogether; the fish can easily tear nets and injure the fishers who try to untangle and release them. One system already in place tags the Atlantic sturgeon with small, sound-emitting transmitters that track their movement and allow fisheries and others on the bay to give the sturgeon a wide berth.

But that acoustic tagging information doesn’t provide enough coverage – and it can’t predict where the sturgeon will go next. With that in mind, a NASA Earth Applied Sciences team collaborated with Oliver, as well as with DNREC, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), and Delaware State University to come up with a more complete warning system.

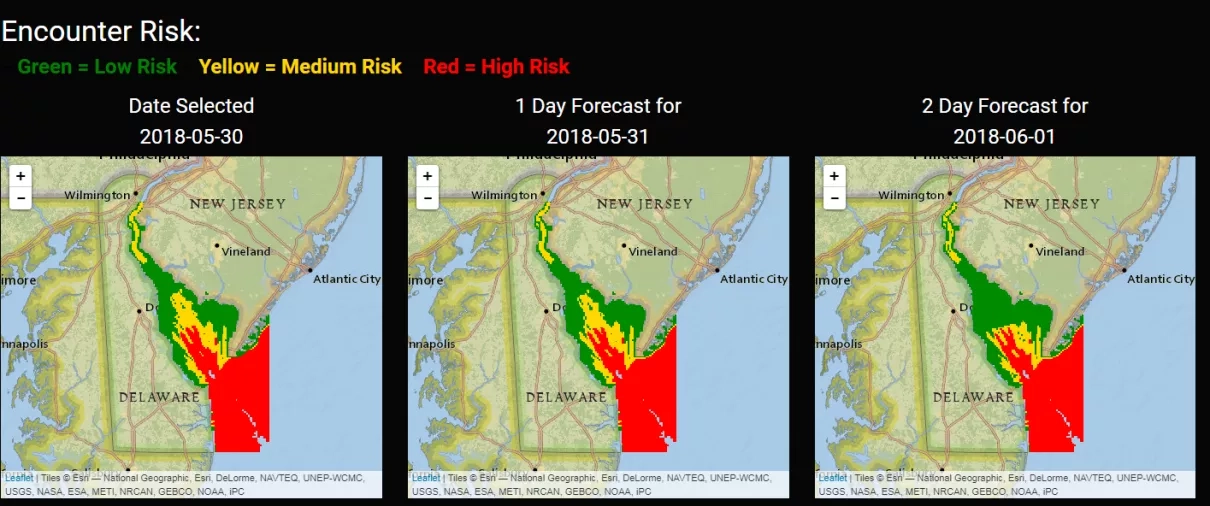

The project team integrated environmental variables such as sea surface temperature, sea floor topography, and ocean color data with the acoustic tagging observations to help track and forecast adult sturgeon swimming through Delaware waters. With this information, the team developed the Atlantic Sturgeon Forecast Warning System, a free “heads-up” for avoiding costly interactions. This system, which can deliver messages through a web application, online flyers, or text-based updates to a mobile device, alerts interested parties to the risk of encountering sturgeon in the Delaware River and Bay, and even issues a risk forecast three days out.

For DNREC, this improved system is ideal. “The application provides a needed regulatory fact-check on habitat usage within specific portions of the habitat in real time,” said Hale. “Also, the tool allows for our commercial fishers to avoid time and money spent detangling nets of relatively large animals, subsequently minimizing potential gear damage and down time.”

Buoyed by this project’s success, Oliver emphasized, “We think the merger of the biotelemetry [data] and the Earth observations is a powerful method for doing marine spatial management. We hope that this approach is a model that is taken by both researchers and management in the future.”

This story is part of our Space for U.S. collection. To learn how NASA data are being used in your state, please visit nasa.gov/spaceforus.