It’s big, it’s beautiful and it’s wild – three good reasons why Alaska is called the Last Frontier. Adding to its reputation as an untamed land are more than 130 volcanoes, which comprise about 80% of all active volcanoes in the United States.

Breathtaking to look at while dormant, when Alaska’s volcanoes awaken they can pose a serious threat to residents and industries.

“The goal of all the agencies that respond to volcanic eruptions is to make sure that lives and property are protected, but just as importantly, [we] try to minimize disruptions to the air traffic system,” said David Schneider, a geophysicist for U.S. Geological Survey’s (USGS) Alaska Volcano Observatory. “The main hazard from eruptions in Alaska are explosive volcanic eruptions that put ash clouds up into the air. There’s about 25,000 [airline] passengers per day that transit over volcanoes in Alaska.”

The hazard comes from microscopic silica in volcanic ash that can scratch aircraft windshields and shut down the engines. A prime example of volcanic ash impact is the 2010 eruption of Iceland’s Eyjafjallajökull volcano, which caused a massive worldwide aviation delay. The far-reaching ash plume stranded millions of airline passengers, causing an estimated economic impact of $5 billion from the 6-day shutdown.

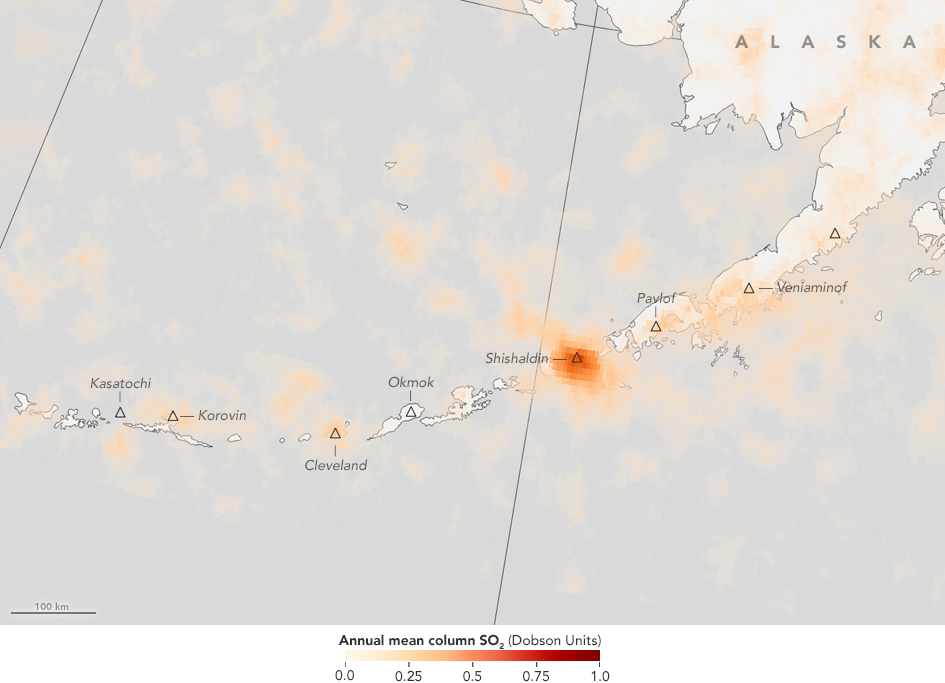

Recently, a joint project of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) and NASA gave both scientists and forecasters more accurate tools to protect planes and passengers from volcanic ash while maintaining airline operations. By integrating satellite data, volcanic clouds are tracked by their chemical composition. In particular, the satellites detect the sulfur dioxide (SO2) composition of the ash clouds to identify their location and where they’re going. The satellites can also map the clouds in 3D as upper atmospheric winds push them across the globe.

The European Space Agency and the nine worldwide Volcanic Ash Advisory Centers are charged with analyzing this innovative ash data and distributing it to federal regulators, air navigation providers and airlines. With a newly added satellite data receiving station in Fairbanks, Alaska, users now receive the data in near real-time.

“The new capability of receiving observations here directly in Alaska is a great improvement,” NOAA's Schneider said. “We’re able to get the data within tens of minutes after [a satellite’s] overpass, and there are many cases where, by tracking the SO2, you’re able to get a better picture of the full extent of the volcanic cloud.”

“The new capability of receiving observations here directly in Alaska is a great improvement. We’re able to get the data within tens of minutes after [a satellite’s] overpass.”

—David Schneider, U.S. Geological Survey

Forecasters can also narrow the geographic extent of the advisories. “When we issue volcanic ash advisories, we are not always very clear on precisely where the ash is located,” said Don Moore of the Anchorage Volcanic Ash Advisory Center. “Instead of drawing a large polygon that describes where the hazard may be, this will allow us to fine-tune that.”

As forecasters receive this new volcanic ash information more quickly, it allows them to provide pilots with updated information sooner. “Aircraft move in excess of 500 miles per hour (805 kilometers per hour),” Schneider said, “so the faster you can get data in, process it, and have it available for analysis, the better you are.”

This story is part of our Space for U.S. collection. To learn how NASA data are being used in your state, please visit nasa.gov/spaceforus.