The U.S. Corn Belt is home to the nation’s most productive soils, the product of millennia of deep-rooted prairie grasses. It includes a vast area of the midwestern United States, roughly covering western Indiana, Illinois, Iowa, Missouri, eastern Nebraska, and eastern Kansas, in which corn (maize) and soybeans are the dominant crops.

Hundreds of miles above the Corn Belt, NASA satellites provide critical views of the region. They’re helping scientists study soil loss over time and develop tools to support farmers as they adopt and manage conservation techniques.

After the corn harvest last fall, Illinois farmer Paul Jeschke planted a fraction of his fields with cereal rye: 60 acres of the 4,500 he farms with his wife, nephew and brother-in-law. In the coming months, the rye would sprout into a rolling sea of grass. Below ground, it would feed soil microbes and scavenge nitrogen leftover from the corn, preventing it from entering the Illinois River 10 miles away. Above, the thick stand would protect the field from the wind and water that strip soil.

“This is a radically different farming system, and it takes an adventurous mindset to risk growing a crop in such a manner,” Jeschke said. Cover crops are grown not to be harvested, but to shield and improve soil when a cash crop isn’t growing. Conservation efforts like Jeschke's are significant, says Laura Gentry, a University of Illinois adjunct assistant professor and director of water quality research at the Illinois Corn Growers Association. She is a partner with NASA Harvest, NASA’s food security and agriculture program within the Earth Science division. "Whatever the hurdles are, it's worth it to help farmers address them.”

Bit by bit, wind, water and gravity naturally can strip away valuable topsoil, but extreme weather and tillage—overturning soil to prepare it for planting—accelerate erosion. Eroded soils are less productive and leach nutrients. Soil also stores carbon: the remnants of once-living things like plants, microbes and insects. As one of Earth’s biggest carbon sinks, meaning an area that absorbs large amounts of carbon, soil represents an important part of the global carbon cycle.

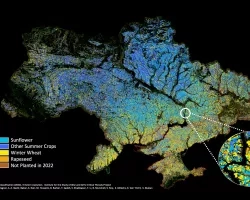

Views from space help researchers study big-scale issues and measure the success of new ways of farming that helps keep soils healthy. NASA’s MODIS, or Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer, instruments on board the Terra and Aqua satellites, along with the joint NASA-U.S. Geological Survey’s Landsat satellites, provide regular observations across the region.

More about how NASA is working with farmers like Jeschke to preserve soil can be found at the NASA.gov feature, Shoring up the Corn Belt's Soil Health with NASA Data.

NASA at Your Table is a series of articles, videos and other features highlighting how NASA data, satellites and other assets are in use to preserve the nation's agriculture.