SPACE-BASED TECHNOLOGY AND CITIZEN SCIENTISTS ARE ANSWERING THAT AGE-OLD QUESTION—DOES A BEAR SMILE IN THE WOODS?

NASA satellites are helping Wisconsin develop a clearer picture of its diverse and abundant fauna. Through a partnership project called Snapshot Wisconsin, scientists and managers are focusing on better wildlife management by linking spaceborne views with keen eyes on the ground.

Picture This

Snapshot Wisconsin is a statewide trail camera project run by the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources (WDNR) that monitors mammalian and avian wildlife in partnership with citizen scientists. Its goals are twofold: “The first is to provide a consistent and cost-effective method of monitoring all types of wildlife throughout the year—and all across Wisconsin—for the purpose of wildlife decision-making,” said Jennifer Stenglein, a wildlife scientist with the WDNR. “The second is to involve citizens in the process of wildlife monitoring.”

And that’s where the trail cameras come into play. A trail camera is a mounted, automated camera that captures an image, or sequence of images, when activated. Cameras can snap pictures at prescribed times or when sensors detect something moving in front of the camera.

For the Snapshot Wisconsin project, more than 800 Wisconsinites have volunteered to set up and monitor nearly 1,000 trail cameras and upload their photos to the Zooniverse database—an online platform where citizen scientists provide data used by wildlife managers and professional researchers. Once the photos are in this database, anyone around the globe can help count and classify the species caught on camera— which means a birder in Bermuda or a hunter in Hungary can assist in Wisconsin’s wildlife management.

Not Just Badgers

Since its inception, the project has snapped more than 17 million photos. Of these millions, about 250,000 provide valuable images of Wisconsin wildlife for Zooniverse’s database. In this repository, you can find photos of beavers, bobcats, badgers, and black bears. Snapshots of everything from a prickle of porcupines to grazing grouse and frolicking foxes can be seen here. The site has yet to archive a skunk taking a selfie (a smellfie?)— though it certainly seems that the occasional doe-eyed deer is posing for the camera.

“Without images collected from space, it would be incredibly difficult to reliably predict and map the distribution and abundance of species.” - JOHN CLARE

Ultimately, the project team hopes to have about 5,000 cameras dotting the state; an average of about 70 cameras per county. The team is acutely aware that trail cameras can only capture so much of Wisconsin’s 54,000 square miles of land. And snapshots alone can’t help the WDNR understand the environmental factors that determine the distribution and abundance of the state’s wildlife.

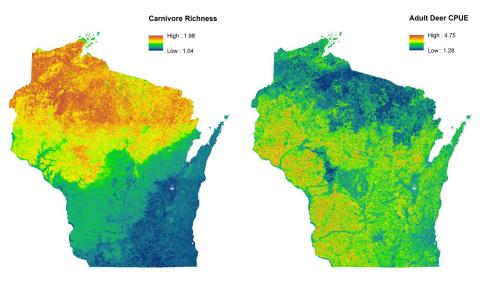

As a partner of Snapshot Wisconsin, NASA brought its satellite fleet into the equation to provide that missing information. “NASA data are critical to making maps. Even though we have a lot of trail cams, those are still only a sample of the landscape,” stressed Phil Townsend of UW-Madison, the principle investigator of this project. “We know that what we measure from NASA imagery—such as snow cover, forest cover and fragmentation— explains where animals are at different times of the year, as well as their behavior…it also helps us better understand what drives animal use of the landscape.”

A Wider Perspective

Specifically, the project team tapped into Earth-observing instruments on the Aqua, Terra, and Landsat satellites for the data it needed. “What’s great about these sensors is that they collect data regularly, and over large continuous spaces, which we can link to the trail camera data to figure out what’s happening at the camera locations and the spaces in between cameras,” said John Clare, project team member and PhD student with UWMadison’s Department of Forest and Wildlife Ecology. “Two of the more important sensors for our research are Landsat’s Thematic Mapper and the MODIS sensors.” He continued, “These sensors are complementary—MODIS’s greater temporal resolution makes it more useful for detecting environmental changes like plant green-up, while Landsat’s greater spatial resolution makes it more useful for detailed mapping of relatively static environmental attributes, like the location of forests, wetlands, and prairies.”

As for the kind of guidance the team might give wildlife managers, Clare provided Wisconsin’s snowshoe hare as an example. “[The] snowshoe hare seems to be declining due to snow loss,” he noted. “We might find that hare persistence is associated with brushy, young forest and we might suggest implementing forestry practices to promote this habitat to keep the species around.” This guidance would ideally not just help the hare to survive, but allow it—and other species—to thrive.

Forward Focused

Looking for more ways to use that wider perspective for small-scale applications, the Snapshot Wisconsin team is now looking to bring NASA satellite data down to Earth for assisting decision-making at the county level—this time, for forecasting future scenarios. “The white-tailed deer population in Wisconsin is estimated using a formula to get a prehunt and post-hunt population size,” Stenglein said. To do this, wildlife managers monitor the populations in each of the state’s Deer Management Units, which roughly correspond to each county of Wisconsin. The formula uses several inputs, including the annual number of harvested bucks and the fawn-to-doe ratios in August and September.

“Fawn-to-doe ratios are known to be affected by overwinter weather in the forested portions of Wisconsin, and NASA satellites can help us make those links at camera locations and the spaces in-between,” she explained. With this added environmental data, the team could build predictive models for better population estimates. “Having accurate deer population estimates for each Deer Management Unit is foundational for the decision-making cycle of quota setting and determining the annual hunting season structure.”

And with this better overall view of Wisconsin’s deer population, Stenglein hopes that, down the road, the Snapshot Wisconsin project will assist the WDNR in its aerial deer surveys. “The contribution of Snapshot Wisconsin will at least compliment the surveys that are already being done,” she pointed out. “Ideally there will be some cases where Snapshot Wisconsin can even replace these routine surveys, thereby saving staff time and money.”

With this fleet of NASA satellites and sensors now supporting the WDNR’s wildlife management, Clare reiterated, “The remote-sensing data has really improved our understanding of the distribution of certain species that might be difficult to study over large extents, and we’ve been able to identify certain environmental correlates that haven’t been previously well-established.” This added pair of eyes-in-the-sky is truly helping the WDNR make space for Wisconsin’s fauna.