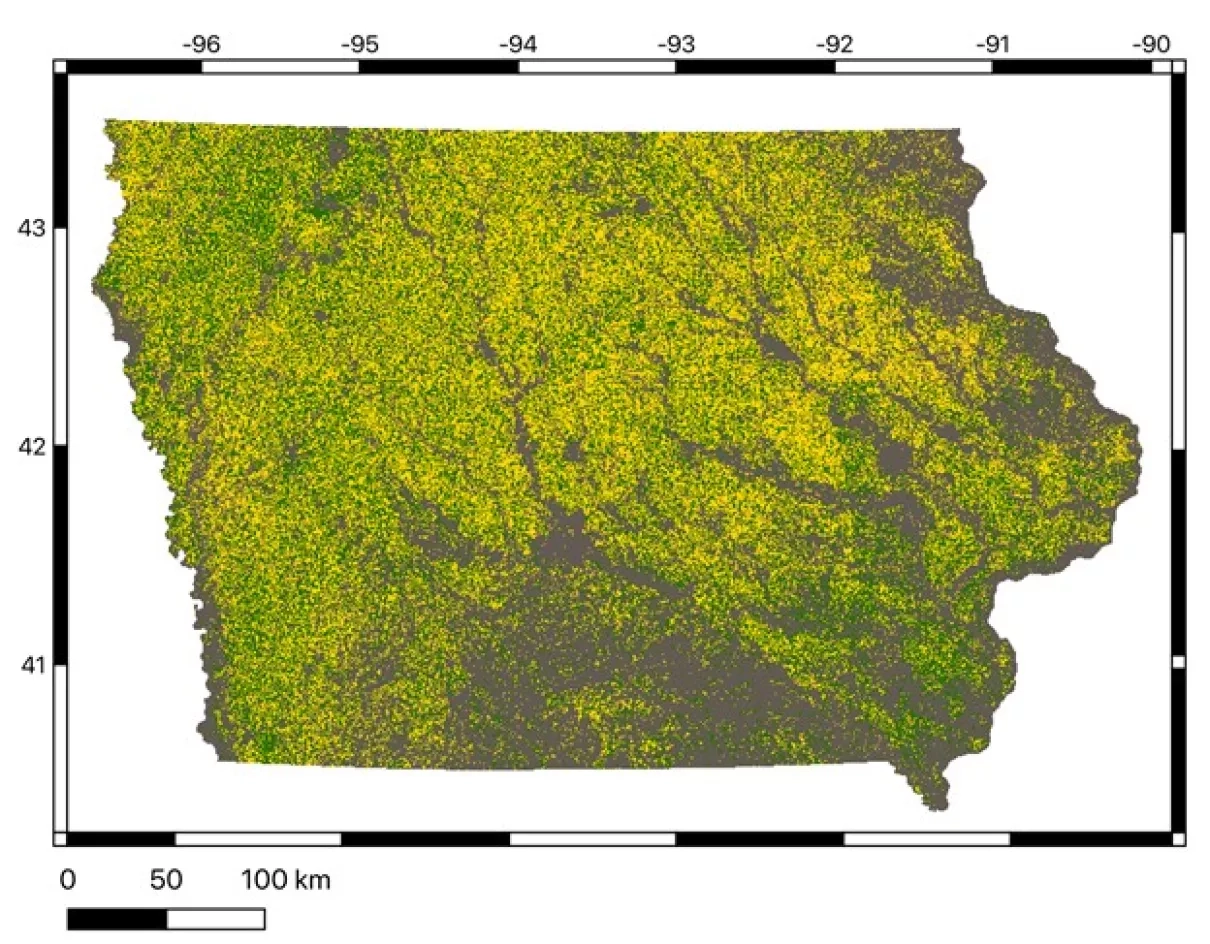

In the image below, can you spot which crops are growing and how healthy they are? Maybe not, but that’s exactly what Hannah Kerner is teaching computers to do, and these machine learning algorithms lead to predictions that help government leaders and farmers make more informed decisions about food security.

Kerner is an assistant research professor at the University of Maryland (UMD) and is the machine learning lead and U.S. domestic co-lead for NASA Harvest, NASA Earth Applied Sciences’ agriculture and food security program. Her work with NASA Harvest earned her a spot on Forbes’ 2021 30 Under 30 in science.

In 2019, the World Health Organization estimated that about two billion people experience moderate or severe food insecurity worldwide — and Africa is particularly hard hit. The problem is expected to get worse as climate change continues. Extreme weather and climate-driven events like drought, flooding, severe storms and pests create far-reaching economic, social and humanitarian crises with increasing frequency.

“Climate and agriculture are in this intertwined negative feedback loop,” Kerner said. “Agriculture is one of the biggest drivers of greenhouse gas emissions, and yet at the same time agriculture and food security are one of the most vulnerable sectors to climate change. And so, one continues to worsen the other.”

To help governments and small-scale farmers — called smallholder farmers — better prepare for the challenges a changing climate poses to crops, Kerner and her team work with local partners to develop machine learning algorithms with satellite data that can identify when, where and what type of crops are growing. This combination of methods and data sources can also be used to characterize crop health, assesses impacts from disasters and identify agricultural practices.

The image above is the kind of data that Kerner and her team use to train the machine learning algorithms. Satellite images are incredibly complex. A satellite image includes a lot more data than the type of images often used by machine learning applications, like the Facebook algorithm that recognizes your face in photos and suggests you tag yourself.

“That is a difficult task of course, to identify your face out of billions of faces in the world or other objects,” Kerner said. “But typically, these images are static in time and space. They only have three spectral channels (red, green, and blue). In satellite images, it’s very different.”

To process a satellite image, Kerner’s algorithms must look at a wide spectrum of both visible and invisible colors and assess changes through time and space. They also have to account for clouds and other artifacts that can disrupt the image signal. There’s a lot of variability to take into account — and everything is both inter-related and constantly changing.

It’s not the complexity of the algorithms that presents the biggest challenge for Kerner and her team, however. They’re more limited by the availability of ground-level data, called ground truth data. Kerner needs reliable access to that ground truth data to train her models and ensure the predictions are accurate.

“Working on this application of machine learning with NASA Harvest has underscored the importance of ethics in machine learning and model trustworthiness, and really validating your models and your outputs to make sure they are trustworthy,” Kerner said. "If Facebook guesses that your face is actually your friend’s face, no harm no foul, right? But if we guess that crops are doing great and they’re not, that’s a big problem.”

Making things even more complex is that the smallholder farmers that are most at risk of food insecurity are often in remote or rural areas where ground truth data can be difficult to obtain. Engaging with local stakeholders, in addition to field research, have been crucial to bridging these data gaps. Kerner relies on ground truth data gathered by fellow NASA scientists like Catherine Nakalembe and others in her research group or publicly available data sets.

“People assume that you can tell what type of crop is growing from a satellite image,” Kerner said. “They are very surprised to learn that you cannot look at an image from Landsat-8 or Sentinel-2 and say, ‘Corn is growing here.’” Although Kerner and her team can make educated guesses based on which crops grow in certain regions or at certain times, they can’t know for certain without eyes on the ground. “This is why we rely so much on ground truth information, even if it’s only telling us what type of crop is growing somewhere,” she continued. “Of course the farmers know what type of crop they’re growing in their fields. But this is not public information — there are very few public data sets about this.”

Kerner and her NASA Harvest colleagues are particularly active in sub-Saharan Africa, where food security has suffered greatly in recent years due to disasters like cyclones, droughts, extreme flooding, landslides and in 2020, the most severe locust infestation in 70 years. The analyses they glean from their machine learning algorithms help government decision-makers and farmers in these countries bridge the information gap and make decisions on food security and supply, humanitarian aid needs and imports and exports.

One of their biggest recent successes has been supporting a Togo government program called YOLIM, an interest-free digital loan program designed to boost food production across smallholder farms. Towards the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, Kerner and her colleagues received a request to help them boost agricultural production for smallholder farms that feed local people. They needed reliable information on where these farms are located and who was doing the farming across different administrative districts across the country. Kerner and her team used machine learning and satellite observations from Landsat 8, Sentinel-2 and Sentinel-1 together with commercially available fine-resolution data from the private company Planet to create a high-resolution, 10 meter per pixel map of cropland. The team provided this detailed data about the size and location of croplands to Togo government officials, who then used it to inform their decisions on how to distribute the loan program funds.

Seeing the positive effects of her work being used in Togo is what drives Kerner to do what she does.

“Ever since I learned how to code, I felt like it was this amazing tool to make an impact anywhere in the world right from your own computer keyboard,” she said. “I think in general throughout my life, I’ve felt compelled to do something that matters while I’m alive. Combining these two interests and using code to create solutions that help people and the planet or enable scientific discovery is really where I see that fit for myself.”

While Kerner has been interested in computer science, space and humanitarian impact for a long time, it wasn’t until college that she found a way to connect the three. She attended a talk by the Harvard Humanitarian Institute on how they used satellite data to identify the location of mass graves and evidence of other crimes against humanity. That talk drove home the impact satellite data could have on furthering humanitarian work and showed her a path forward for combining her passions. Kerner has been doing data-driven, impactful work ever since.

In both her role as an assistant research professor and in her volunteer work, Kerner strives to help youth and adults to achieve their educational and professional goals. As a first-generation college student who paid her own way through school — Kerner’s parents both served in the US Navy before entering the travel industry — she knows first-hand the challenges other aspiring first-generation college students face.

“Something my parents instilled in me was the idea that I was capable of anything so long as I had the will to do it, which I really took to heart. If I see something I want to help do or fix then I feel like I can and will do that through my actions,” Kerner said. “I think my volunteering and community activities go back to the idea that — cheesy as it is — you only live once. I feel an obligation to try and give what resources and knowledge I have to those lacking resources the most. I also feel that having an education and lucrative skills like coding is a pathway to so many opportunities and a network of supporters to help you achieve your goals and meet your and your family's needs. That is why I've focused a lot on education as well as tech skills and access.”

One of the organizations Kerner is involved with is From Prison Cells to PhD, a nonprofit organization that helps people with criminal convictions through advocacy, mentoring and policy change. There, she serves as a tutor for currently or previously incarcerated people working to reach their education goals. Although many community meetings have stalled during the pandemic, Kerner also actively participates in her community.

She works with the Sharp-Leadenhall neighborhood in Baltimore, Md. to write grants for community funds for programs like senior fitness and entertainment, youth education and civic engagement. She also volunteers at Whitelock Community Farm in Baltimore, Md. “It’s too small to see in satellite images — I’ve tried,” she joked.

When interacting with both her students and youth in her community, Kerner takes inspiration from an unlikely source: U.S. singer and actor Janelle Monáe. “She inspires me to not only do excellent work with your particular trade but also to be yourself while doing it, to be unapologetic about who you are and what you believe in,” she said. “I try to put this into practice with my students, to make them feel like they can pursue what interests them and what is important to them and that they deserve to have a seat at the table. This is especially important for students who identify as women or BIPOC (black, indigenous and people of color).” Studies show that women earn 57% of all undergraduate degrees but make up only 18% of all undergraduate computer and information science degrees. Only 10% of students majoring in computer science identify as black.

Although her schedule is typically jam packed, in her free time Kerner enjoys reading, hiking with her dog Pixel, baking and scuba diving. Her favorite place to dive is in Hawaii at Electric Beach, also known as Kahe Point, where she can swim and watch sea turtles, huge schools of fish and — when she’s lucky — dolphins swim by the warm water blowing from a nearby pipe.

Whether she’s exploring the Earth herself or analyzing it through Earth data, Kerner’s passion for Earth’s beauty and drive to effect positive change shines through in everything she does.

To learn more about Kerner’s work with NASA Harvest, check out her projects on the NASA Harvest website.