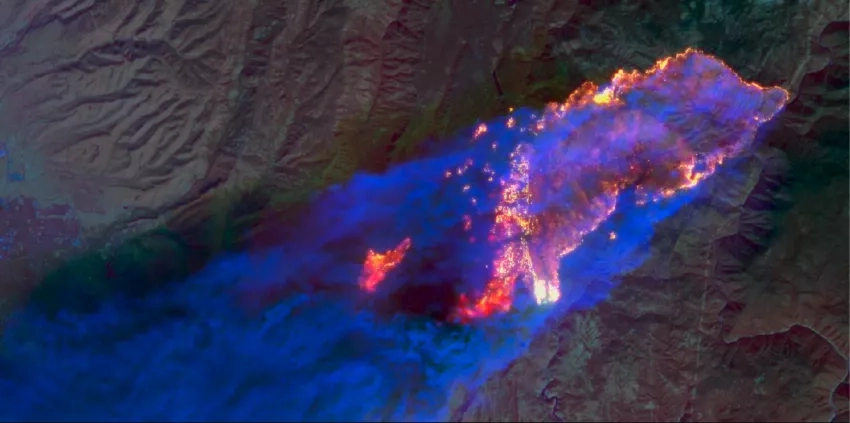

A spark from faulty electrical equipment, and then flames. That was all it took to ignite the 2018 Camp Fire in Northern California, which became the deadliest and most destructive fire in California’s history. In particular, on November 9, 2018, Californians and the rest of America woke up to the news that the wildfire had already consumed 70,000 acres of land 90 miles north of Sacramento overnight. Over the next two weeks, first responders and other organizations tracked the fire closely on the ground, while Brady Helms monitored it from a different vantage point: the skies.

A disaster management coordinator with the NASA Applied Sciences Disasters program area, Helms was tracking the fires’ spread via satellite data. Of the 115 disaster responses he’s been involved with over almost three years with Disasters — ranging from earthquakes and oil spills to hurricanes and floods — the Camp Fire is the one that continues to stand out in his mind as one of the most significant of his career. The severity of the fire was part of what made it significant, but there was more to it than that. It also coincided with the start of his time with Disasters. As the first disaster response in his new position, Helms said the Camp Fire was a real eye opener.

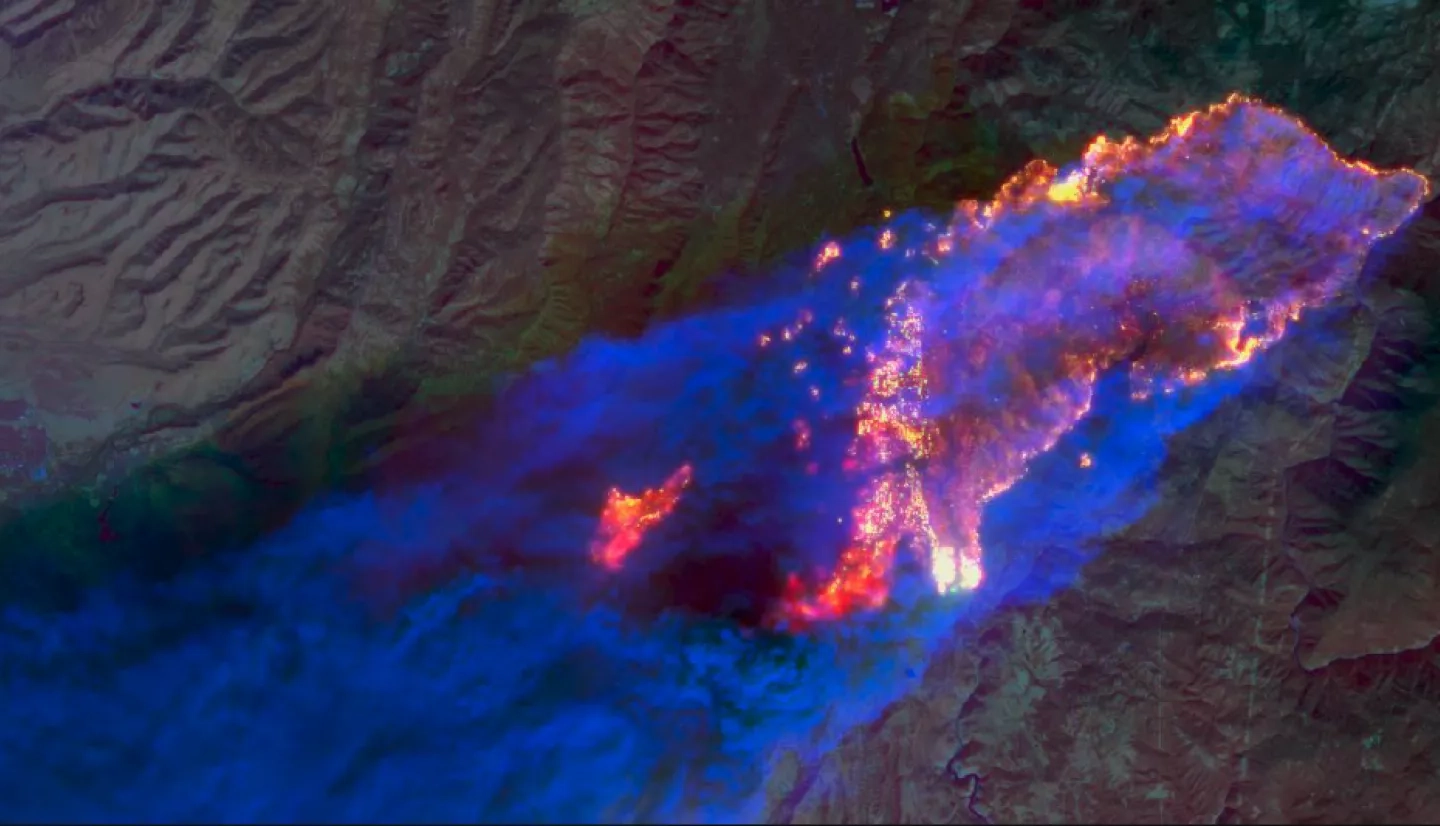

“The Camp Fire sticks with me because that’s the point where I truly began to understand the value of the remote sensing data this program specializes in,” Helms said. “The fires were so huge and so fast moving that it was impossible for folks on the ground to have a full understanding of what exactly was happening. Our ability to convert the data taken from space by the satellites into images that were easy to understand and showed the full scope of the incident was valuable to me and the decision-makers.”

Helms and his team within Disasters provided the sky-high views that played a valuable role in helping the folks on the ground both respond to the current situation and prepare for future risks. Helms monitored the situation tirelessly from beginning to end — and even after the flames died out, he was watching for landslides and other secondary risks.

At the Fire’s Outbreak: Monitoring the Spread

Helms first heard the news of the Camp Fire beginning on the Friday of Veteran’s Day weekend — and in two days, the Disasters team had mobilized their group of subject matter experts. In those early days, their first goal was to determine how they could be of the most help to the different organizations and responders combatting the wildfires.

Since NASA is a research-based organization, it coordinates with 24/7 monitoring centers like the California Office of Emergency Services, CAL FIRE and the California National Guard, who find and relay information to the folks responding to the disaster. Armed with this information, first responders can consider the situation from all angles when making decisions.

“When you’re in a disaster situation on the ground, information is usually piecemeal,” Helms said. “The role of the emergency operations center is to give you a complete operating picture. That way, you understand whether there are other disasters occurring nearby — especially in the case of fires, there is usually more than one. Without comprehensive information, you may not understand that there are conflicting disasters which change your priorities and your resource availability.”

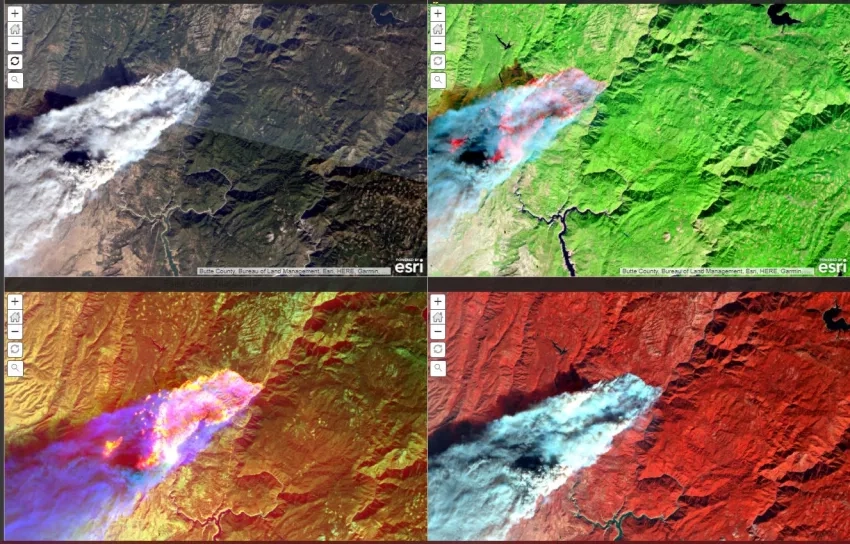

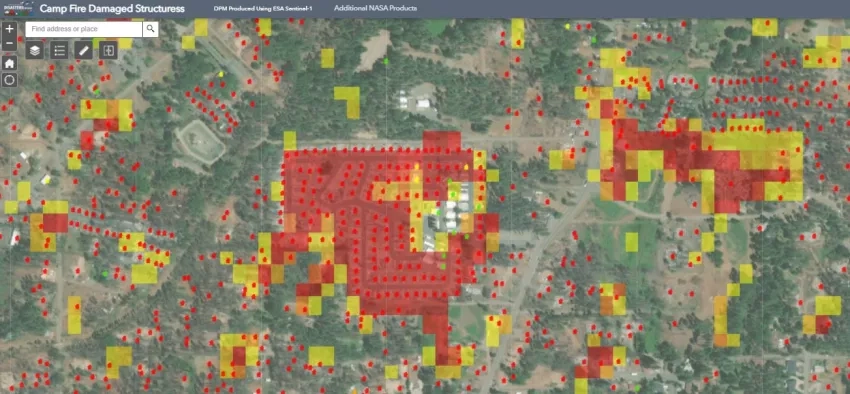

To piece together a more complete picture, Helms and his team relied on data from myriad satellites and products including Sentinel-1, ASTER, NASA’s Black Marble HD product, UAVSAR, Landsat 8, and FIRMS fire progression data. Combining these different sources allowed them to tell a full story — not just what was going on in the present, but how the disaster was evolving over time.

In the case of the 2018 Camp Fire, there were an overwhelming number of pieces to the story. Being so new to the program, this was Helms’s first wildfire. Before joining the NASA Applied Sciences Program, he worked at NASA’s Kennedy Space Center, where he focused on one area of responsibility. But in his new role, he needed to monitor every aspect of the unfolding disaster.

“When you read about a wildfire in the news, you just see one piece of the event at a time," Helms said. “So they talk about the fire, and then they talk about evacuations, and then air quality, and then debris flows from rains that may fall after the fire. When you’re getting your information from multiple sources, it can seem like there are just singular events that seem to occur one right after another.”

But in reality, all of those things are interconnected, with each part of the fire impacting the other. Helms said the Camp Fire opened his eyes to how connected the impacts of a wildfire are —and drove home just how valuable remote sensing is in these situations. Remote sensing helps disaster management personnel understand exactly how the different aspects of a wildfire connect in a given situation, which allows them to look ahead at what might occur next. This kind of foresight allows them to be proactive instead of reactive and plan for different risks ahead of the curve.

As the Fire Raged: Partnering with Local Agencies to Prevent Loss of Life

Being able to look ahead is a critical part of fire response. It helps decision makers mobilize in a way that minimizes the loss of life and destruction of property. Although Helms and his team don’t have a direct role in decision making, those goals are always top of mind as they parse and pass on data. In order to be successful, they must start with a solid understanding of stakeholders’ needs.

One of the organizations Helms worked with throughout the wildfire was a long-standing NASA partner, the California National Guard and State Guard Incident Awareness and Assessment team. They combined NASA’s satellite data with state agencies’ field data on damage assessments and burn severity to gain a fuller situational awareness of the wildfire’s spread.

“NASA does a great job describing the metadata about the products they create,” said Phil Beilin, the geographic information systems coordinator for California State Guard. “However, there is occasionally a need to translate the data categories or units into a more decision-making friendly format, or a need for clarification on where the dataset is more or less accurate. Brady and his team have regularly connected our team with the appropriate NASA team members to provide that clarity or recategorization where possible. He provides the interface between translation to and from the scientists who create the data and the decision makers who need to know how and where to use it.”

“I enjoy working with Brady greatly,” Beilin continued. “He has a combination of can-do mentality, patience and genuine interest in developing an efficient workflow for making NASA products understood and as available as possible to our team and the state agencies we work with.”

One of the things that makes Helms such a natural at this kind of work is that he’s kindled a passion for weather his whole life. He would sit at the window or stand outside watching storms roll through his hometown until his parents pulled him inside. “I always wanted to be a meteorologist, but I’m not good at calculus —which is pretty much a requirement for that kind of work — so I had to find a new career path,” Helms said.

When he enrolled in an introductory emergency management course in college, he was instantly hooked. Helms said it unlocked a passion he didn’t know he had for making sure people are ready for things. Although he didn’t end up getting a degree in emergency management at the time, a major tornado changed his trajectory for good. Helms was working as a funeral director when the tornado ripped through his area in the middle of the night killing 27 people. The tragic loss of life propelled him back into college. He finished his emergency management degree, determined to help figure out how to prevent loss of life from disasters wherever possible.

Once the Flames Abated: Reflecting on the Past to Prepare for the Future

Monitoring the 2018 Camp Fire, Helms and his team worked 12-hour days, even on weekends, for about two weeks. They wrapped up just before Thanksgiving once the wildfire was nearly contained, and the first thing Helms did was take a breath — he felt like he’d been holding it all that time. But even though he took some time off, Helms’s work on the wildfire wasn’t over. After the initial event for any disaster, the Disasters program area’s work is twofold: they monitor for cascading events and gather to discuss the disaster response— what went well, and what they can improve.

In the case of the Camp Fire, Helms was particularly looking at landslide risks. Disasters offers a near real-time monitoring program called the Global Landslide Nowcast, which predicts risk based on rainfall. Helms helped their partners integrate the platform into their maps. They could combine the Global Landslide Nowcast layer with NASA’s maps of burned areas, various damage assessments and rainfall assessments from the National Weather Service. By combining these data sources, emergency operations centers had a good idea where landslides were more likely — and issued warnings to anyone living nearby.

“Obviously we cannot predict exactly when and where a landslide would occur, but our data helped those stakeholders in California inform residents that there could be an increased risk of landslides and to be prepared just in case that were to materialize,” Helms said.

Helms also participated in an after-action review, both with his own team and with different partners in California. Their goal was to discuss their response to the wildfire and decide what they could improve and what they wanted to use for future responses. Helms spent three days in California afterwards for an intensive workshop to discuss how NASA and emergency operations centers could better integrate and support each other. One of the biggest lessons Helms learned from the Camp Fire was the importance of developing partnerships with stakeholders — before a disaster even occurs.

“There were a couple of stakeholders we sent some of our products to [during the wildfires], and they’d never seen them before,” Helms explained. "They were unable to use them because they didn’t understand what they were looking at and we didn’t have time – nor did they – to sit down and explain during the disaster. This highlighted the need to collaborate prior to disasters with potential stakeholders so they have a full understanding of what we can do, and what they’re looking at when they use our data and products for a disaster.”

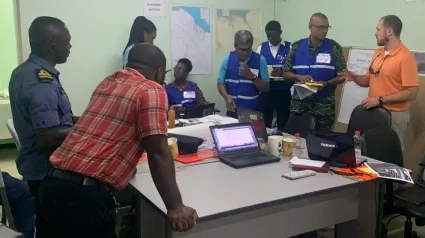

Helms and his team have taken this lesson to heart. In early June of 2021, Helms flew to California for a three-day prescribed burn exercise to learn more about the situations first responders face and the questions they ask while battling the flames. They’ve also applied this lesson to other types of disasters. NASA has made strong partnerships in the Caribbean — including the U.S. Southern Command (SOUTHCOM), the Guyana Civil Defence Commission and the Caribbean Disaster Emergency Management Agency — to help them prepare for and respond to oil spills, flooding and hurricanes. And this is just the start, too. Helms and his team are actively seeking to build partnerships across the globe so they can help decision makers prepare for whatever disasters might come their way.

“Everyone on this planet is at risk from disaster of one type or another,” Helms said. “Our work shows the big picture so there’s a full understanding of what’s going on, not just on the ground but from a systems perspective – how the different Earth systems come together to create the hazards that we face day in and day out on the planet.

“We also show what’s possible. We are a research agency, so we’re always trying to combine different data sets or understand and fill data gaps so our work can inform the full cycle of emergency management – mitigation, preparedness, response, and recovery – and the risks associated with disasters around the world,” Helms said. “Once we understand the risk, and root cause of the risk, then we can become resilient to the hazards and the risks we face.”