Faisal Hossain’s mission is to expand access to information on the world’s water. As a hydrologist and professor of civil and environmental engineering at the University of Washington in Seattle, Hossain uses satellite data to track water resources. He’s also helping develop new tools that will make that work easier. For example, Hossain serves as applications lead for the science team of the Surface Water Ocean Topography (SWOT) mission, which is jointly led by NASA and the French space agency CNES. We caught up with Hossain to find out what drives him, what excites him about the new SWOT mission and how he hopes satellite data will empower the public. Here’s five questions we put to Hossain:

How did you first become interested in studying water resources?

It was during my childhood growing up in various countries with contrasting climates and challenges related to water. I was born in Bangladesh, a country that receives almost 90 percent of its wet season flow from upstream countries and is quite dry for the rest of the year. Later, in Libya, I used to watch in awe how this arid country was tapping into water trapped under the Saharan desert by building thousands of miles of underground pipes in the so-called Great Man-Made River project.

You’ve stated that your mission is to make access to information on water a fundamental right. How did you develop this goal? What are the biggest challenges to achieving that mission?

During my college days in India, I had this epiphany during a journey back home when I was literally chased by floods. Due to lack of access to forecasts of the weather and floods, a typical two-day journey took me four days. And it dawned on me how important access to information on water is to empower us all to make the best proactive decisions—in my case about when and where to travel.

The challenge of this mission is more on the equity part—access rather than availability. Data on water in all forms—on surface, underground, and precipitation—are aplenty and continuously maintained around the world using ground or satellite networks. However, the available data is not accessible equitably to all. Some do not have access due to lack of connectivity or awareness. Others do not have the necessary training to access the data. To me the equity and inclusivity part are the biggest challenges that we haven’t yet resolved completely.

What aspect of your recent project monitoring water in Bangladesh makes you most proud?

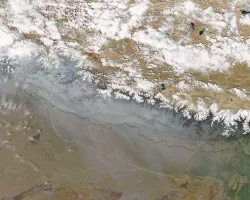

I’m most proud of the fact that we were able to show, for the first time, the volume of surface water Bangladesh experiences in the flood prone northeastern region. We have known all along where there is too much water. But we had never been able to put a finger on how much volume of water changes as the region experiences its seasonal cycles. Now, we can use, for example, gauges and satellites from Tamlin Pavelsky’s citizen science project, Lake Observations by Citizen Scientists & Satellites, or LOCSS. This allows us to estimate the volume of water, which turns out to be the equivalent of water in Lake Mead in the U.S. What is more fascinating is that we have been able to track the volume routinely during unusually wet years, such as 2022. Consequently, the Bangladesh water authorities are now empowered with this newfound knowledge and are exploring various planning options for the country’s water security.

What excites you about new remote sensing tools like the upcoming SWOT mission?

SWOT is the first mission ever that will tell us not only where the surface water is, but also changes in elevation. This lets us estimate volume changes right away. Currently we have to jury rig a solution like combining data from various other satellites at different times and making generalizations. Previous research showed us the added value of measuring water elevation with area—and it tells us that SWOT will be a game changer when it comes to routine monitoring of water volume change in lakes and reservoirs.

You’ve also made films and children’s books. What drives your desire to reach audiences beyond the scientific community?

I believe the communication of science and the value of the research we do is essential to help the public understand why our work is important. Research papers, posters, talks and seminars are mostly preaching to the choir or to a select group with necessary expertise. If we are to mobilize the whole world and empower them with scientific advancements (such as SWOT), then I believe we have to meet the public where they are with different types of communications such as films, children’s books etc.

What advice do you have for young scientists coming up in the field?

Pursue your passion. Think beyond getting your amazing research work published (which is important). Think of how to break your work down and promote it so that it can be assimilated into everyday life. Think about the cultural, social and equity aspects that are getting in the way. If you do not do this, no one else will do it for you, and your work may never reach its true potential for societal impact.

More about Faisal Hossain's Applied Sciences work can be found at the articles Upstream Solutions and Water for Life.